6. Hash Functions

Hash functions are functions that take some input an compress them to produce an output of fixed size, usually just called hash or digest. A desired property of hash function is collision resistance.

Hash functions are also used in hash table data structures, and for data structures, it isn’t a huge problem if there is a collision. Although the search time may be affected, there are ways to handle conflicting hashes for each data structure.

But cryptographic hash functions are different. They should avoid collisions, since some adversary will attack in order to find collisions and break the system. Thus cryptographic hash functions are much harder to design.

Collision Resistance

Intuitively, a function $H$ is collision resistant if it is computationally infeasible to find a collision for $H$. Formally, this can be defined also in the form of a security game.

Definition. Let $H$ be a hash function defined over $(\mathcal{M}, \mathcal{T})$. Given an adversary $\mathcal{A}$, the adversary outputs two messages $m_0, m_1 \in \mathcal{M}$.

$\mathcal{A}$ wins the game if $H(m_0) = H(m_1)$ and $m_0 \neq m_1$. The advantage of $\mathcal{A}$ with respect to $H$ is defined as the probability that $\mathcal{A}$ wins the game.

\[\mathrm{Adv}_{\mathrm{CR}}[\mathcal{A}, H] = \Pr[H(m_0) = H(m_1) \wedge m_0 \neq m_1].\]If the advantage is negligible for any efficient adversary $\mathcal{A}$, then the hash function $H$ is collision resistant.

With a collision resistant hash function, we can do many things. For example, password hashing is a very common example. Instead of storing the plaintext password, the plaintext is hashed, and the hash is stored. One of the reasons for doing this is for privacy. Even the developers who can access the database shouldn’t be able to obtain the plaintext password, and the plaintext password will be safe even if the database is leaked.

When the user logins, the password user entered will be hashed to compare with the stored hash in the server. It is obvious that we need collision resistant hashes, since if not, a malicious user can login using the collision.

Another desirable property would be the one-wayness of $H$, that it should be hard to find the preimage of any hash. It can be shown that collision resistance implies one-wayness.1

MAC Domain Extension

One possible use of hash function is for extending the domain of MACs. A MAC scheme is usually defined for a fixed block size, so for longer messages, we need other constructions. This is where hash functions can come in.

Let $\Pi = (S, V)$ be a MAC scheme defined over $(\mathcal{K}, \mathcal{M}, \mathcal{T})$, and let $H : \mathcal{M}’ \rightarrow \mathcal{M}$ be a hash function, where $\mathcal{M}’$ is usually larger than $\mathcal{M}$. A naive way to construct a MAC would be to apply the hash first to compress the message and then sign it. It turns out that this new construction is a secure MAC if $\Pi$ is secure and $H$ is collision resistant.

Theorem. Let $\Pi’ = (S’, V’)$ be a MAC defined over $(\mathcal{K}, \mathcal{M}’, \mathcal{T})$. Let

\[S'(k, m) = S(k, H(m)), \quad V'(k, m, t) = V(k, H(m), t).\]If $\Pi$ is a secure MAC and $H$ is collision resistant, then $\Pi’$ is a secure MAC.

For any efficient adversary $\mathcal{A}$ attacking $\Pi’$, there exist a MAC adversary $\mathcal{B} _ \mathrm{MAC}$ attacking $\Pi$ and an adversary $\mathcal{B} _ \mathrm{CR}$ attacking $H$ such that

\[\mathrm{Adv}_{\mathrm{MAC}}[\mathcal{A}, \Pi'] \leq \mathrm{Adv}_{\mathrm{MAC}}[\mathcal{B}_\mathrm{MAC}, \Pi] + \mathrm{Adv}_{\mathrm{CR}}[\mathcal{B}_\mathrm{CR}, H].\]

Proof. See Theorem 8.1.2

Intuitively, suppose that the MAC scheme $\Pi’$ is insecure. During the MAC security game, $\mathcal{A}$ can either find or not find a collision for $H$. If $\mathcal{A}$ found a collision, $H$ is not collision resistant. If $\mathcal{A}$ didn’t find a collision, then $\Pi$ must be broken. Thus we have a contradiction.

But in reality, this construction is not used very often. We need a secure MAC and a collision resistant hash function, so it is hard to implement.

Attacks on Hash Functions

There are specific attacks that exploit the internal mechanism of some specific hash function, but we only cover generic attacks that work for any given hash function.

A very simple attack would be the brute force attack. If the hash is $n$ bits, then the attacker can hash $2^n+1$ arbitrary messages to get a collision, by the pigeonhole principle. But usually $n$ is large enough that performing this computation is infeasible.

Birthday Attacks

Actually, the attacker doesn’t have to hash that many messages. This is because of the birthday paradox.

Let $N$ be the size of the hash space. (If the hash is $n$ bits, then $N = 2^n$)

- Sample $s$ uniform random messages $m_1, \dots, m_s \in \mathcal{M}$.

- Compute $x_i \leftarrow H(m_i)$.

- Find and output a collision if it exists.

Lemma. The above algorithm will output a collision with probability at least $1/2$ when $s \geq 1.2\sqrt{N}$.

Proof. We show that the probability of no collisions is less than $1/2$. The probability that there is no collision is

\[\prod_{i=1}^{s-1}\left( 1-\frac{i}{N} \right) \leq \prod_{i=1}^{s-1} \exp\left( -\frac{i}{N} \right) = \exp\left( -\frac{s(s-1)}{2N} \right).\]So solving $\exp\left( -s(s-1)/2N \right) < 1/2$ for $s$ gives approximately $s \geq \sqrt{(2\log2)N} \approx 1.17 \sqrt{N}$.

In the above proof, we assume that $H$ is uniform. But in reality, $H$ might be biased, but it can be shown that collision probability is minimized when $H$ is uniform, so the above argument holds.

Note that birthday attacks can be done entirely offline. The adversary doesn’t have to interact with any users of the system, so adversaries can invest huge computing resources to find a collision, without anybody noticing. Thus, offline attacks are considered more dangerous than online attacks that require many interactions.

Merkle-Damgård Transform

Now we want to construct collision resistant hash functions that work for arbitrary input length. Thanks to the Merkle-Damgård transform, we can start from a collision resistant hash function that works for short messages.

The Merkle-Damgård transform gives as a way to extend our input domain of the hash function by iterating the function.

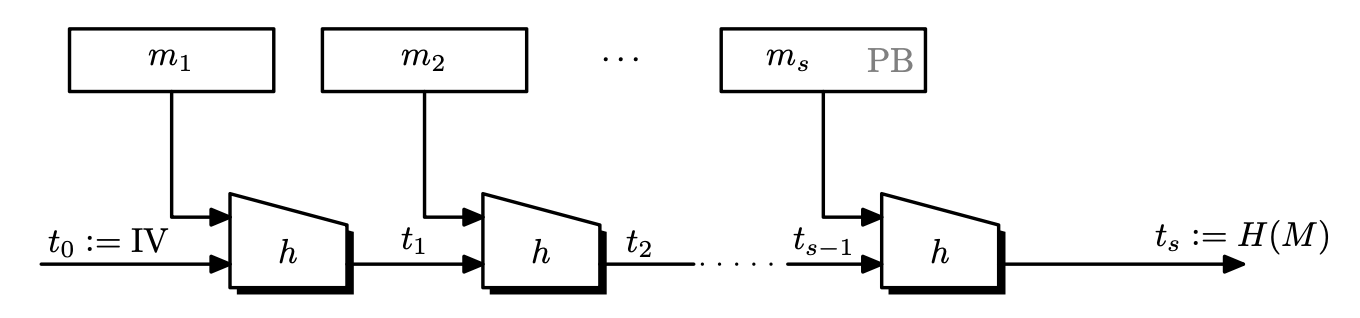

Definition. Let $h : \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^n \times \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^l \rightarrow \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^n$ be a hash function. The Merkle-Damgård function derived from $h$ is a function $H$ that works as follows.

- Given an input $m \in \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^{\leq L}$, pad $m$ so that the length of $m$ is a multiple of $l$.

- The padding block $\mathrm{PB}$ must contain an encoding of the input message length. i.e, it is of the form $100\dots00\parallel\left\lvert m \right\lvert$.

- Then partition the input into $l$-bit blocks so that $m’ = m_1 \parallel m_2 \parallel \cdots \parallel m_s$.

- Set $t_0 \leftarrow \mathrm{IV} \in \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^n$.

- For $i = 1, \dots, s$, calculate $t_i \leftarrow h(t_{i-1}, m_i)$.

- Return $t_s$.

- The function $h$ is called the compression function.

- The $t_i$ values are called chaining values.

- Note that because of the padding block can be at most $l$-bits, the maximum message length is $2^l$, but usually $l = 64$, so it is enough.

- $\mathrm{IV}$ is fixed to some value, and is usually set to some complicated string.

- We included the length of the message in the padding. This will be used in the security proof.

The Merkle-Damgård construction is secure.

Theorem. If $h$ is a collision resistant hash function, then so is $H$.

Proof. We show by contradiction. Suppose that an adversary $\mathcal{A}$ of $H$ found a collision for $H$. Let $H(m) = H(m’)$ for $m \neq m’$. Now we construct an adversary $\mathcal{B}$ of $h$. $\mathcal{B}$ will examine $m$ and $m’$ and work its way backwards.

Suppose that $m = m_1\cdots m_u$ and $m’ = m_1’\cdots m_v’$. Let the chaining values be $t_i = h(t_{i-1},m_i)$ and $t_i’ = h(t_{i-1}’, m_i’)$. Then since $H(m) = H(m’)$, the very last iteration should give the same output.

\[h(t_{u-1},m_u) = h(t_{v-1}', m_v').\]Suppose that $t_{u-1} \neq t_{v-1}’$ and $m_u \neq m_v’$. Then this is a collision for $h$, so $\mathcal{B}$ returns this collision, and we are done. So suppose otherwise. Then $t_{u-1} = t_{v-1}’$ and $m_u = m_v’$. But because the last block contains the padding, the padding values must be the same, which means that the length of these two messages must have been the same, so $u = v$.

Now we have $t_{u-1} = t_{u-1}’$, which implies $h(t_{u-2}, m_{u-1}) = h(t_{u-2}’, m_{u-1}’)$. We can now repeat the same process until the first block. If $\mathcal{B}$ did not find any collision then it means that $m_i = m_i’$ for all $i$, so $m = m’$. This is a contradiction, so $\mathcal{B}$ must have found a collision.

By the above argument, we see that $\mathrm{Adv} _ {\mathrm{CR}}[\mathcal{A}, H] = \mathrm{Adv} _ {\mathrm{CR}}[\mathcal{B}, h]$.

Attacking Merkle-Damgård Hash Functions

See Joux’s attack.2

Davies-Meyer Compression Functions

Now we only have to build a collision resistant compression function. We can build these functions from either a block cipher, or by using number theoretic primitives.

Number theoretic primitives will be shown after we learn some number theory.3 An example is shown in collision resistance using DL problem (Modern Cryptography).

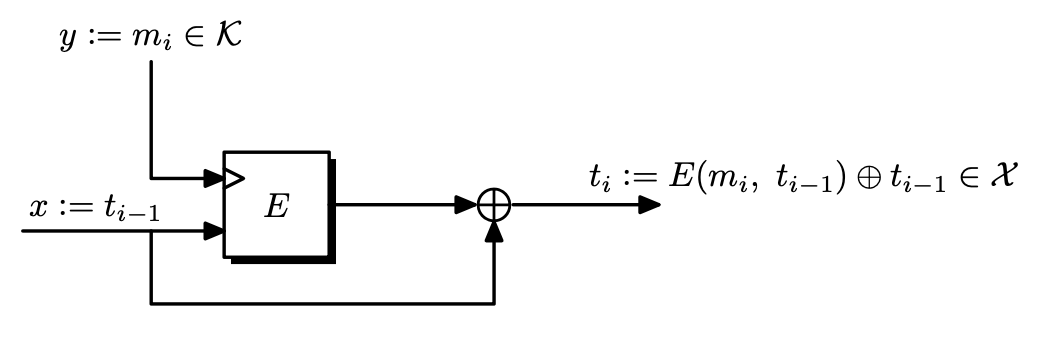

Definition. Let $\mathcal{E} = (E, D)$ be a block cipher over $(\mathcal{K}, X, X)$ where $X = \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^n$. The Davies-Meyer compression function derived from $E$ maps inputs in $X \times \mathcal{K}$ to outputs in $X$, defined as follows.

\[h(x, y) = E(y, x) \oplus x.\]

Theorem. Suppose $\mathcal{E}$ is an ideal cipher.4 Then finding a collision for $h$ takes $\mathcal{O}(2^{n/2})$ evaluations of $(E, D)$.

Proof. Check Theorem 8.4.2

Due to the birthday attack, we see that this bound is the best possible.

There are other constructions of $h$ using the block cipher. But some of them are totally insecure. These are some insecure functions.

\[h_1(x, y) = E(y, x) \oplus y, \quad h_2(x, y) = E(x, x \oplus y) \oplus x.\]Also, just using $E(y, x)$ is insecure.

Secure Hash Algorithm (SHA)

This is a family of hash functions published by NIST.

- 1993: SHA0

- 1995: SHA1

- 2001: SHA2-256 and SHA2-512 (most widely used)

- 2015: SHA3-256 and SHA3-512

There are known attacks for SHA0 and SHA1, so use at least SHA2.

SHA1 and SHA2 uses Merkle-Damgård and Davies-Meyer compression function. But if we use just AES, then the block size is $128$ bits, meaning that birthday attacks take $\mathcal{O}(2^{64})$, which is a bit small. So SHA2 uses a different block cipher called SHACAL-2 that uses $256$ bit blocks.

HMAC

We needed a complicated construction for MACs that work on long messages. We might be able to use the collision resistance of hash functions and build a MAC with it.

Some Approaches

Here are a few approaches. Suppose that a compression function $h$ is given and $H$ is a Merkle-Damgård function derived from $h$.

Recall that we can construct a MAC scheme from a PRF, so either we want a secure PRF or a secure MAC scheme.

Prepending the Key

Define $S(k, m) = H(k \parallel m)$. This is insecure by length extension attacks. Given $H(k \parallel m)$, one can compute $H(k \parallel m \parallel m’)$ for any $m’$, resulting in forgery.

Appending the Key

Define $S(k, m) = H(m \parallel k)$. This is vulnerable to an offline attack on $h$. If there is a collision on $h$, then $h(\mathrm{IV}, m) = h(\mathrm{IV}, m’)$ for some $m \neq m’$. Then $S(k, m) = S(k, m’)$ which results in forgery.

Envelope Method

Define $S(k, m) = H(k \parallel M \parallel k)$. This can be proven to be a secure PRF under reasonable assumptions. See Exercise 8.17.2

Two-Key Nest

Define $S((k_1,k_2), m) = H(k_2 \parallel H(k_1 \parallel m))$. This can also be proven to be a secure PRF under reasonable assumptions. See Section 8.7.1.2

This can be thought of as blocking the length extension attack from prepending the key method.

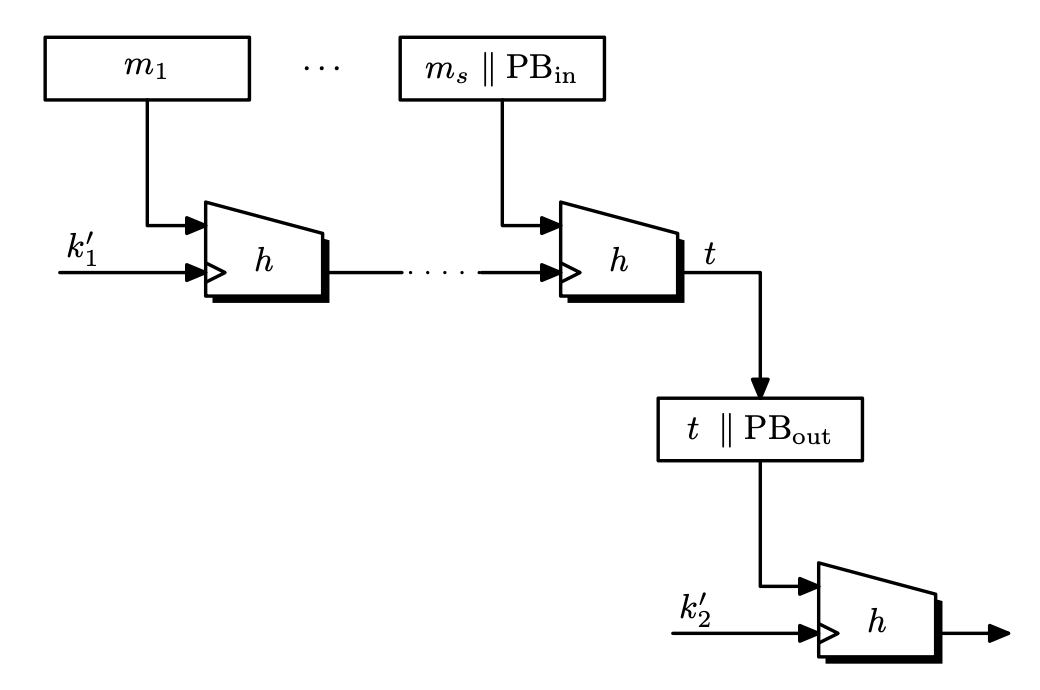

HMAC

This is a variant of the two-key nest, but the difference is that the keys $k_1’, k_2’$ are not independent. Choose a key $k \leftarrow \mathcal{K}$, and set

\[k_1 = k \oplus \texttt{ipad}, \quad k_2 = k\oplus \texttt{opad}\]where $\texttt{ipad} = \texttt{0x363636}…$ and $\texttt{opad} = \texttt{0x5C5C5C}…$. Then

\[\mathrm{HMAC}(k, m) = H(k_2 \parallel H(k_1 \parallel m)).\]The security proof given for two-key nest does not apply here, since $k_1$ and $k_2$ are not independent. With stronger assumptions on $h$, then we almost get an optimal security bound.

The Random Oracle Model

Motivation

Some constructions using cryptographic hash functions cannot be proven secure only using the collision resistance assumption.

A conservative way to solve this problem would be to construct schemes that can be proven secure, using reasonable assumptions about the hash function. But it may be hard to find such schemes and they may be less efficient than existing approaches that haven’t been formally proven. On the other hand, it is unacceptable to use a cryptosystem without a security proof, even though attackers have been unsuccessful.

Introducing an idealized model offers a middle ground to this. The model is not real, and reality is far from ideal. But as long as the model is reasonable, proofs under the idealized model is better than nothing. Proof with idealized model lets us understand the scheme better.

Random Oracle Model

The random oracle model is a model that treats a cryptographic hash function as a truly random function. In this model, there is a public, random function $H$, that can be evaluated only by querying the oracle.

The random oracle model also provides a formal method that can be used to design and validate cryptosystems using the following approach.

- Design a scheme and prove that it is secure in the random oracle model.

- During implementation, replace the random oracle with a cryptographic hash function.

We hope that the cryptographic hash function used in step 2 is good enough to mimic a random oracle. Then the proof of security in the random oracle model would be still valid in the real world.

But there are schemes that can be proven insecure when instantiated with hash functions, even if they were proven secure in the random oracle model. Also, any hash function cannot behave like a random oracle/function. So a security proof in the random oracle model suggests that some scheme has no internal design flaws, but it is not enough to claim security of the scheme in the real world.

There is a subtle detail here, refer to this question on cryptography SE. ↩︎

A Graduate Course in Applied Cryptography ↩︎ ↩︎2 ↩︎3 ↩︎4 ↩︎5

These are rarely used since they rely on prime numbers, and prime numbers are expensive. Also block ciphers are blazingly fast compared to computing integers. ↩︎

We treat the block cipher as a family of random permutations. i.e, for each $k \in \mathcal{K}$, $E(k, \cdot)$ is a random permutation. ↩︎