7. Key Exchange

In symmetric key encryption, we assumed that the two parties already share the same key. We will see how this can be done.

In symmetric key settings, a user has to agree and store every key for every other user, so if there are $N$ users in the system, $\mathcal{O}(N^2)$ keys are to be stored in the system. But these keys are secret information, so they have to be handled with care. With so many keys, it is hard to store and manage them securely.

Distributing a key requires a lot of care. The two parties need a secure channel beforehand, or have to meet physically in person to safely exchange keys. But for open systems, physical meetings cannot be arranged and users are not aware of each other before communicating.

In summary, symmetric key cryptography has at least three problems.

- It is hard to distribute keys securely.

- It is hard to storing and managing many secret keys securely.

- Symmetric key cryptography cannot be applied to open systems.

Problems 1 and 2 can be solved partially using trusted third parties (TTP), but such TTPs become a single point of failure, and is usually used only in a single organization.

Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange (DHKE)

We need a method to share a secret key. For now, assume that the adversary only eavesdrops, and does not tamper with the message.

Generic Description and Requirements

Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol allows two parties to generate a shared secret key, without establishing a physical meeting. Here is a generic description of the protocol.

We have two functions $E(\cdot)$ and $F(\cdot, \cdot)$.

- Alice chooses a random secret $\alpha$ and computes $E(\alpha)$.

- Bob chooses a random secret $\beta$ and computes $E(\beta)$.

- Alice and Bob exchange $E(\alpha), E(\beta)$ over an insecure channel.

- Using the given information, Alice and Bob both compute a shared key $F(\alpha, \beta)$.

Alice only knows $\alpha, E(\beta)$, and Bob only knows $\beta, E(\alpha)$. With the given information for each party, they compute $F(\alpha, \beta)$ and use it as a shared key. Also, since Alice and Bob are currently exchanging keys, $E(\alpha)$ and $E(\beta)$ are sent over an insecure channel. Then the eavesdropper can see $E(\alpha), E(\beta)$.

Overall, for this protocol to be secure, $E$ and $F$ should at least satisfy the following.

- $E$ is easy to compute.

- Given $\alpha$ and $E(\beta)$, it is easy to compute $F(\alpha, \beta)$.

- Given $E(\alpha)$ and $\beta$, it is easy to compute $F(\alpha, \beta)$.

- Given $E(\alpha)$ and $E(\beta)$, it is hard to compute $F(\alpha, \beta)$.

- $E$ must be a one way function.

The first three conditions are for the communicating parties, and is sort of a correctness condition that Alice and Bob can agree on the same key efficiently. The last two conditions are a security condition. It should be hard for the eavesdropping adversary to compute the secret, and that it must be hard to recover $x$ from the value of $E(x)$. Otherwise, the adversary will find $\alpha$ or $\beta$ and compute $F(\alpha, \beta)$.

To implement the above protocol, we need two functions $E$ and $F$ that satisfy the above properties. We rely on the hardness of number theoretic problems to implement this.

DHKE Protocol in Detail

Let $p$ be a large prime, and let $q$ be another large prime dividing $p - 1$. We typically use very large random primes, $p$ is about $2048$ bits long, and $q$ is about $256$ bits long.

All arithmetic will be done in $\mathbb{Z}_p$. We also consider $\mathbb{Z} _ p^ *$ , the unit group of $\mathbb{Z} _ p$. Since $\mathbb{Z} _ p$ is a field, $\mathbb{Z} _ p^ * = \mathbb{Z} _ p \setminus \left\lbrace 0 \right\rbrace$, meaning that $\mathbb{Z} _ p^ *$ has order $p-1$.

Since $q$ is a prime dividing $p - 1$, $\mathbb{Z}_p^*$ has an element $g$ of order $q$.1 Let

\[G = \left\langle g \right\rangle = \left\lbrace 1, g, g^2, \dots, g^{q-1} \right\rbrace \leq \mathbb{Z}_p^*.\]We assume that the description of $p$, $q$ and $g$ are generated at the setup and shared by all parties. Now the actual protocol goes like this.

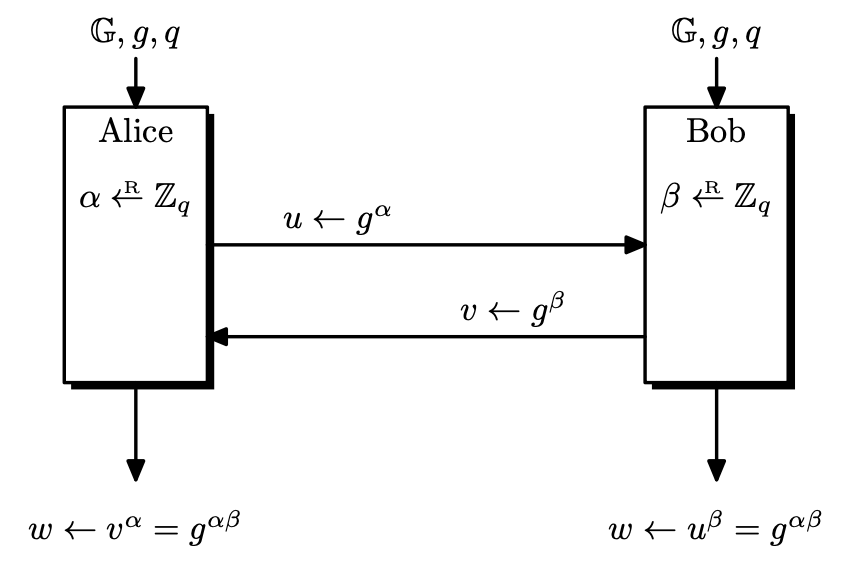

- Alice chooses $\alpha \leftarrow \mathbb{Z}_q$ and computes $g^\alpha$.

- Bob chooses $\beta \leftarrow \mathbb{Z}_q$ and computes $g^\beta$.

- Alice and Bob exchange $g^\alpha$ and $g^\beta$ over an insecure channel.

- Using $\alpha$ and $g^\beta$, Alice computes $g^{\alpha\beta}$.

- Using $\beta$ and $g^\alpha$, Bob computes $g^{\alpha\beta}$.

- The secret key shared by Alice and Bob is $g^{\alpha\beta}$.

It works!

Security of the DHKE Protocol

The protocol is secure if and only if the following holds.

Let $\alpha, \beta \leftarrow \mathbb{Z}_q$. Given $g^\alpha, g^\beta \in G$, it is hard to compute $g^{\alpha\beta} \in G$.

This is called the computational Diffie-Hellman assumption. As we will see below, this is not as strong as the discrete logarithm assumption. But in the real world, CDH assumption is reasonable enough for groups where the DL assumption holds.

Discrete Logarithm and Related Assumptions

We have used $E(x) = g^x$ in the above implementation. This function is called the discrete exponentiation function. This function is actually a group isomorphism, so it has an inverse function called the discrete logarithm function. The name comes from the fact that if $u = g^x$, then it can be written as ‘$x = \log_g u$’.

We required that $E$ must be a one-way function for the protocol to work. So it must be hard to compute the discrete logarithm function. There are some problems related to the discrete logarithm, which are used as assumptions in the security proof. They are formalized as a security game, as usual.

$G = \left\langle g \right\rangle \leq \mathbb{Z} _ p^{ * }$ will be a cyclic group of order $q$ and $g$ is given as a generator. Note that $g$ and $q$ are also given to the adversary.

Discrete Logarithm Problem (DL)

Definition. Let $\mathcal{A}$ be a given adversary.

- The challenger chooses $\alpha \leftarrow \mathbb{Z}_q$ and sends $u = g^\alpha$ to the adversary.

- The adversary calculates and outputs some $\alpha’ \in \mathbb{Z}_q$.

We define the advantage in solving the discrete logarithm problem for $G$ as

\[\mathrm{Adv}_{\mathrm{DL}}[\mathcal{A}, G] = \Pr[\alpha = \alpha'].\]We say that the discrete logarithm (DL) assumption holds for $G$ if for any efficient adversary $\mathcal{A}$, $\mathrm{Adv}_{\mathrm{DL}}[\mathcal{A}, G]$ is negligible.

So if we assume the DL assumption, it means that DL problem is hard. i.e, no efficient adversary can effectively solve the DL problem for $G$.

Computational Diffie-Hellman Problem (CDH)

Definition. Let $\mathcal{A}$ be a given adversary.

- The challenger chooses $\alpha, \beta \leftarrow \mathbb{Z}_q$ and sends $g^\alpha, g^\beta$ to the adversary.

- The adversary calculates and outputs some $w \in G$.

We define the advantage in solving the computational Diffie-Hellman problem for $G$ as

\[\mathrm{Adv}_{\mathrm{CDH}}[\mathcal{A}, G] = \Pr[w = g^{\alpha\beta}].\]We say that the computational Diffie-Hellman (CDH) assumption holds for $G$ if for any efficient adversary $\mathcal{A}$, $\mathrm{Adv}_{\mathrm{CDH}}[\mathcal{A}, G]$ is negligible.

An interesting property here is that given $(g^\alpha, g^\beta)$, it is hard to determine if $w$ is a solution to the problem. ($w \overset{?}{=} g^{\alpha\beta}$)

Decisional Diffie-Hellman Problem (DDH)

Since recognizing a solution to the CDH problem is hard, we have another assumption that it is hard to distinguish a solution to the CDH problem and a random element from $G$.

Definition. Let $\mathcal{A}$ be a given adversary. We define two experiments 0 and 1.

Experiment $b$.

The challenger chooses $\alpha, \beta, \gamma \leftarrow \mathbb{Z}_q$ and computes the following.

\[u = g^\alpha, \quad v = g^\beta, \quad w_0 = g^{\alpha\beta}, \quad w_1 = g^\gamma.\]- The challenger sends the triple $(u, v, w_b)$ to the adversary.

- The adversary calculates and outputs a bit $b’ \in \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace$.

Let $W_b$ be the event that $\mathcal{A}$ outputs $1$ in experiment $b$. We define the advantage in solving the decisional Diffie-Hellman problem for $G$ as

\[\mathrm{Adv}_{\mathrm{DDH}}[\mathcal{A}, G] = \left\lvert \Pr[W_0] - \Pr[W_1] \right\lvert.\]We say that the decisional Diffie-Hellman (DDH) assumption holds for $G$ if for any efficient adversary $\mathcal{A}$, $\mathrm{Adv}_{\mathrm{DDH}}[\mathcal{A}, G]$ is negligible.

For $\alpha, \beta, \gamma \in \mathbb{Z}_q$, the triple $(g^\alpha, g^\beta, g^\gamma)$ is called a DH-triple if $\gamma = \alpha\beta$. So the assumption is saying that no efficient adversary can distinguish DH-triples from non DH-triples.

Relations Between Problems

It is easy to see that the following holds.

In the order of hardness, DL problem $\gt$ CDH problem $\gt$ DDH problem.

If an adversary can solve the DL problem, it can solve CDH and DDH, so DL problem is harder. It is known that strict inequality holds.

If we assume that an easier problem is hard, we have a strong assumption. That is, it is easier to be broken in the future, because we assumed too much.

DDH assumption $\implies$ CDH assumption $\implies$ DL assumption

Suppose we used the DDH assumption in the proof. If the DDH assumption turns out to be false, proofs using the CDH or DL assumption remain valid.

If we used the DL assumption and it turns out to be false, there will be an efficient algorithm solving the DL problem. Then CDH, DDH problems can also be solved, so proofs using the DDH or CDH assumption will be invalidated. Thus DL assumption is the weakest assumption, since breaking DL will break both CDH and DDH.

Multi-Party Diffie-Hellman

Suppose we want something like a secret group chat, where there are $N$ ($\geq 3$) people and they need to generate a shared secret key. It is known that $N$-party Diffie-Hellman is possible in $N-1$ rounds. Here’s how it goes. The indices are all in modulo $N$.

Each party $i$ chooses $\alpha _ i \leftarrow \mathbb{Z} _ q$, and computes $g^{\alpha _ i}$. The parties communicate in a circular form, and passes the computed value to the $(i+1)$-th party. In the next round, the $i$-th party receives $g^{\alpha _ {i-1}}$ and computes $g^{\alpha _ {i-1}\alpha _ i}$ and passes it to the next party. After $N-1$ rounds, all parties have the shared key $g^{\alpha _ 1\cdots\alpha _ N}$.

Taking $\mathcal{O}(N)$ steps is impractical in the real world, due to many communications that the above algorithm requires. Researchers are looking for methods to generate a shared key in a single round. It has been solved for $N=3$ using bilinear pairings, but for $N \geq 4$ it is an open problem.

Attacking Anonymous Diffie-Hellman Protocol

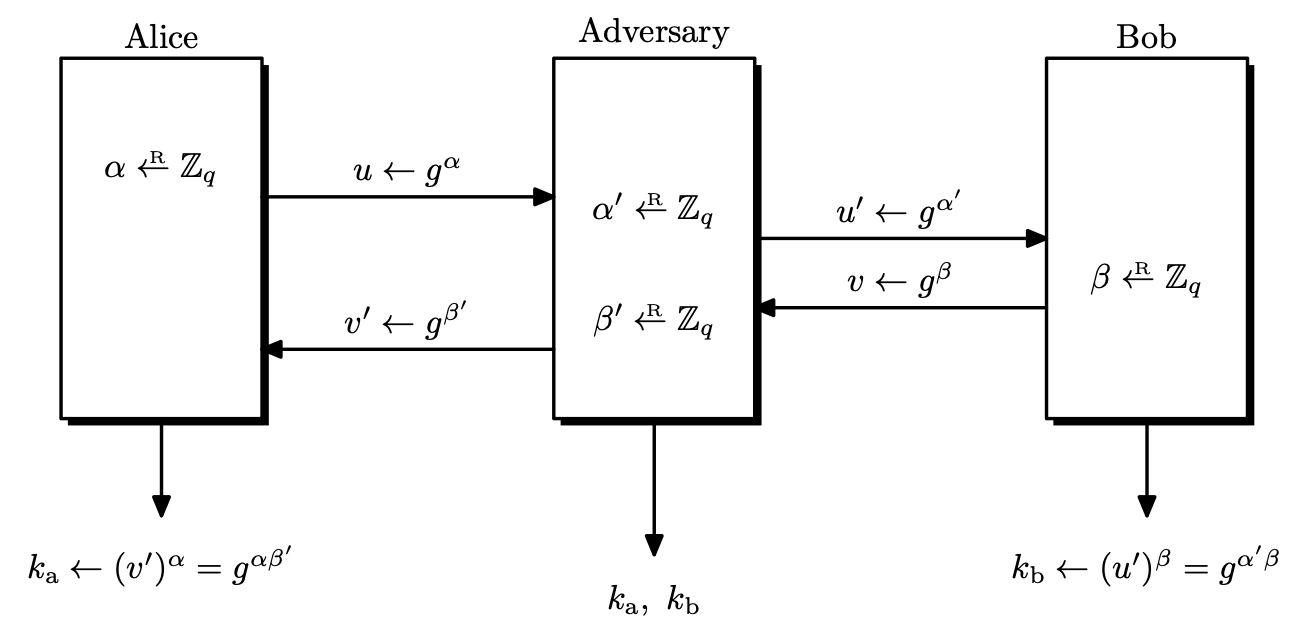

We assumed that the adversary only eavesdrops, but if the adversary carries out active attacks, then DHKE is not enough. The major problem is the lack of authentication. Alice and Bob are exchanging keys, but they both cannot be sure that there are in fact communicating with the other. An attacker can intercept messages and impersonate Alice or Bob. This attack is called a man in the middle attack, and this attack works on any key exchange protocol that lacks authentication.

The adversary will impersonate Bob when communicating with Alice, and will do the same for Bob by pretending to be Alice. The values of $\alpha, \beta$ that Alice and Bob chose are not leaked, but the adversary can decrypt anything in the middle and obtain the plaintext.

Collision Resistance Based on DL Problem

Suppose that the DL problem is hard on the group $G = \left\langle g \right\rangle$, with prime order $q$. Choose an element $h \in G$, and define a hash function $H : \mathbb{Z}_q \times \mathbb{Z}_q \rightarrow G$ as

\[H(\alpha, \beta) = g^\alpha h^\beta.\]If an adversary were to find a collision, then $H(\alpha, \beta) = H(\alpha’, \beta’)$, which implies $g^\alpha h^\beta = g^{\alpha’}h^{\beta’}$, thus $h = g^{(\alpha - \alpha’) / (\beta’ - \beta)}$, calculating the discrete logarithm.

Thus under the DL assumption, the hash function $H$ is collision resistant.

Merkle Puzzles (1974)

Before Diffie-Hellman, Merkle proposed an idea for secure key exchange protocol using symmetric key cryptography.

The idea was to use puzzles, which are problems that can be solved with some effort.

Let $\mathcal{E} = (E, D)$ be a block cipher defined over $(\mathcal{K}, \mathcal{M})$.

- Alice chooses random pairs $(k_i, s_i) \leftarrow \mathcal{K} \times \mathcal{M}$ for $i = 1, \dots, L$.

- Alice constructs $L$ puzzles, defined as a triple $(E(k_i, s_i), E(k_i, i), E(k_i, 0))$.

- Alice randomly shuffles these puzzles and sends them to Bob.

- Bob picks a random puzzle $(c_1, c_2, c_3)$ and solves the puzzle by brute force, trying all $k \in \mathcal{K}$ until some $D(k, c_3) = 0$ is found.

- If Bob finds two different keys, he indicates Alice that the protocol failed and they start over.

- Bob computes $l = D(k, c_2)$ and $s = D(k, c_1)$, sends $l$ to Alice.

- Alice will locate the $l$-th puzzle and set $s = s_l$.

If successful, Alice and Bob can agree on a secret message $s \in \mathcal{M}$. It can be seen that Alice has to do $\mathcal{O}(L)$, Bob has to do $\mathcal{O}(\left\lvert \mathcal{K} \right\lvert)$ amount of work.

For block ciphers, we commonly set $\mathcal{K}$ large enough so that brute force attacks are infeasible. So for Merkle puzzles, we reduce the key space. For example, if we were to use AES-128 as $\mathcal{E}$, then we can set the first $96$ bits of the key as $0$. Then the search space would be reduced to $2^{32}$, which is feasible for Bob.

Now consider the adversary who obtains all puzzles $P_i$ and the value $l$. To obtain the secret message $s_l$, adversary has to locate the puzzle $P_l$. But since the puzzles are in random order, the adversary has to solve all puzzles until he finds $P_l$. Thus, the adversary must spend time $\mathcal{O}(L\left\lvert \mathcal{K} \right\lvert)$ to obtain $s$. So we have a quadratic gap here.

Performance Issues

Suppose we set $L \approx \left\lvert \mathcal{K} \right\lvert$. Then first of all, Alice has to create that many puzzles and send all of them to Bob.

Next, the adversary must spend time $\mathcal{O}(L^2)$, but this doesn’t satisfy our definitions of security, since the adversary has advantage about $1/L^2$ with constant work, which is non-negligible. Also, $L$ must be large enough in practice, which raises the first problem again.

Impossibility Results

It is unknown whether we can get a better gap (than quadratic) using a general symmetric cipher. A partial result was given that quadratic gap is the best possible if we only use block ciphers.2

To get exponential gaps, we need number theory.

By Cauchy’s theorem, or use the fact that $\mathbb{Z}_p^*$ is commutative. Finite commutative groups have a subgroup of every order that divides the order of the group. ↩︎

R. Impagliazzo and S. Rudich. Limits on the provable consequences of one-way permutations. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC), pages 44–61, 1989. ↩︎