12. Zero-Knowledge Proof (Introduction)

- In 1980s, the notion of zero knowledge was proposed by Shafi Goldwasser, Silvio micali and Charles Rackoff.

- Interactive proof systems: a prover tries to convince the verifier that some statement is true, by exchanging messages.

- What if the prover is trying to trick the verifier?

- What if the verifier is an adversary that tries to obtain more information?

- These proof systems are harder to build in the digital world.

- This is because it is easy to copy data in the digital world.

Identification Protocol

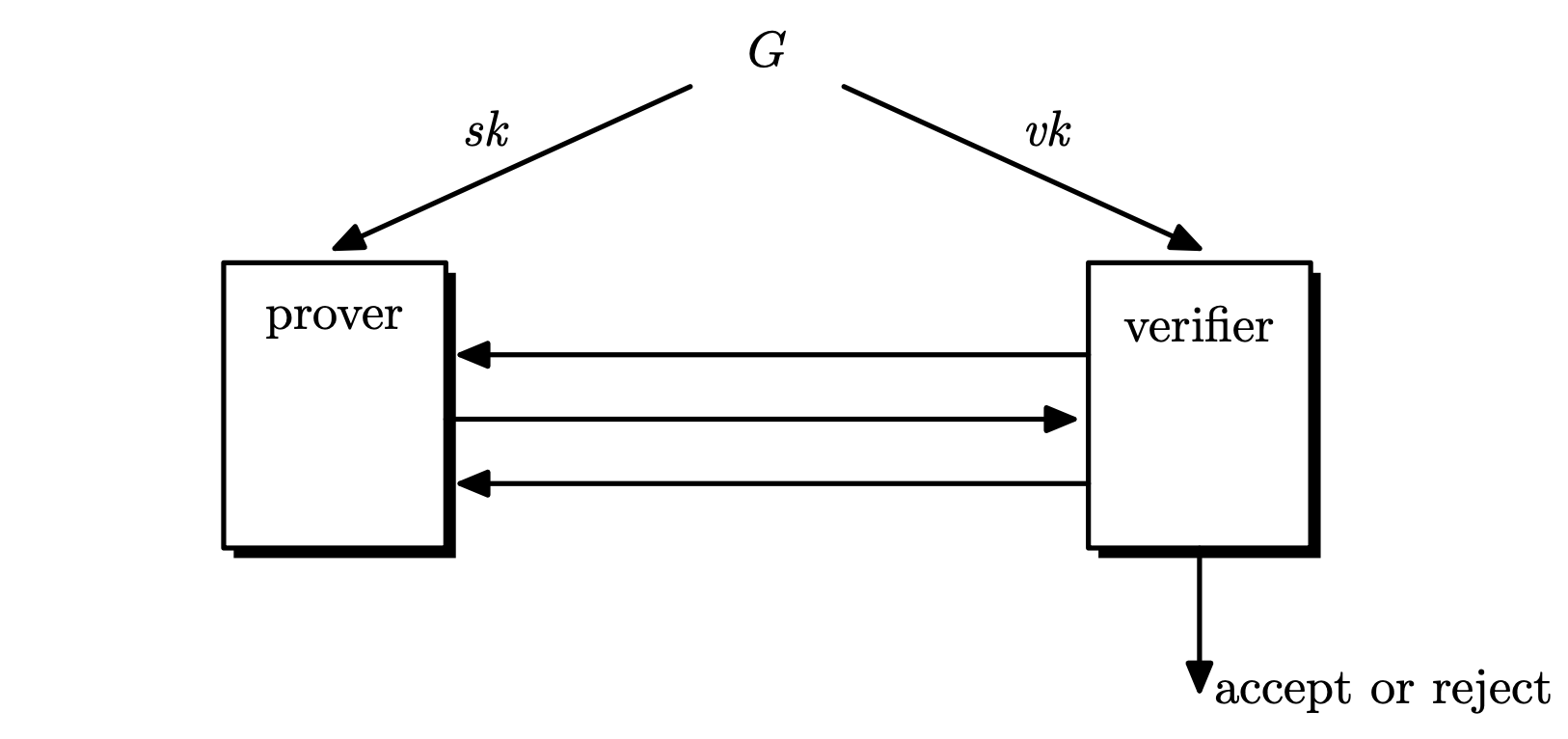

Definition. An identification protocol is a triple of algorithms $\mc{I} = (G, P, V)$ satisfying the following.

- $G$ is a probabilistic key generation algorithm that outputs $(vk, sk) \leftarrow G()$. $vk$ is the verification key and $sk$ is the secret key.

- $P$ is an interactive protocol algorithm called the prover, which takes the secret key $sk$ as an input.

- $V$ is an interactive protocol algorithm called the verifier, which takes the verification key $vk$ as an input and outputs $\texttt{accept}$ or $\texttt{reject}$.

For all possible outputs $(vk, sk)$ of $G$, at the end of the interaction between $P(sk)$ and $V(vk)$, $V$ outputs $\texttt{accept}$ with probability $1$.

Password Authentication

A client is trying to log in, must prove its identity to the server. But the client cannot trust the server (verifier), so the client must prove itself without revealing the secret. The password is the secret in this case. The login is a proof that the client is who it claims to be. What should be the verification key? Setting $vk = sk$ certainly works, but the server learns the password, so this should not be used.

Instead, we could set $vk = H(sk)$ by using a hash function $H$. Then the client sends the password, server computes the hash and checks if it is equal. This method still reveals the plaintext password to the server.

Example: 3-Coloring

Suppose we are given a graph $G = (V, E)$, which we want to color the vertices with at most $3$ colors, so that no two adjacent vertices have the same color. This is an NP-complete problem.

Bob has a graph $G$ and he is trying to $3$-color the graph. Alice shows up and claims that there is a way to $3$-color $G$. If the coloring is valid, Bob is willing to buy the solution, but he cannot trust Alice. Bob won’t pay until he is convinced that Alice has a solution, and Alice won’t give the solution until she receives the money. How can Alice and Bob settle this problem?

Protocol

- Bob gives Alice the graph $G = (V, E)$.

- Alice shuffles the colors and colors the graph. The coloring is hidden to Bob.

- Bob randomly picks a single edge $(u, v) \in E$ of this graph.

- Alice reveals the colors of $u$ and $v$.

- If $u$ and $v$ have the same color, Alice is lying to Bob.

- If they have different colors, Alice might be telling the truth.

- What if Alice just sends two random colors in step $4$?

- We can use commitment schemes so that Alice cannot manipulate the colors after Bob’s query.

- Specifically, send the colors of each $v$ using a commitment scheme.

- For Bob’s query $(u, v)$, send the opening strings of $u$ and $v$.

- What if Alice doesn’t have a solution, but Bob picks an edge with different colors just by luck?

- We can repeat the protocol many times.

- For each protocol instance, an invalid solution can pass with probability $p = \frac{1}{\abs{E}}$.

- Repeat this many times, then $p^n \rightarrow 0$, so invalid solutions will pass with negligible probability.

- Does Bob’s query reveal anything about the solution?

- No, Alice randomizes colors for every protocol instance.

- Need formal definition and proof for this.1

Zero Knowledge Proof (ZKP)

We need three properties for a zero-knowledge proof (ZKP).

- (Completeness) If the statement is true, an honest verifier must accept the fact by an honest prover.

- (Soundness) If the statement is false, no cheating prover can convince an honest verifier, except with some small probability.

- (Zero Knowledge) If the statement is true, no verifier (including honest and cheating) learns anything other than the truth of the statement. The statement does not reveal anything about the prover’s secret.

We define these formally.

Definition. Let $\mc{R} \subset \mc{X} \times \mc{Y}$ be a relation. A statement $y \in \mc{Y}$ is true if $(x, y) \in \mc{R}$ for some $x \in \mc{X}$. The set of true statements

\[L_\mc{R} = \braces{y \in \mc{Y} : \exists x \in \mc{X},\; (x, y) \in \mc{R}}\]is called the language defined by $\mc{R}$.

Definition. A zero-knowledge proof is a protocol between a prover $P(x, y)$ and a verifier $V(x)$. At the end of the protocol, the verifier either accepts or rejects.

In the above definition, $y$ is the statement to prove, and $x$ is the proof of that statement, which the prover wants to hide. The prover and the verifier exchanges messages for the protocol, and this collection of interactions is called the view (or conversation, transcript).

Definition.

- (Completeness) If $(x, y) \in R$, then an honest verifier accepts with very high probability.

- (Soundness) If $y \notin L$, an honest verifier accepts with a negligible probability.

But how do we define zero knowledge? What is knowledge? If the verifier learns something, the verifier obtains something that he couldn’t have computed without interacting with the prover. Thus, we define zero knowledge as the following.

Definition. We say that a protocol is honest verifier zero knowledge (HVZK) if there exists an efficient algorithm $\rm{Sim}$ (simulator) on input $x$ such that the output distribution of $\rm{Sim}(x)$ is indistinguishable from the distribution of the verifier’s view.

\[\rm{Sim}(x) \approx \rm{View}_V[P(x, y) \lra V(x)]\]

For every verifier $V^{\ast}$, possibly dishonest, there exists a simulator $\rm{Sim}$ such that $\rm{Sim}(x)$ is indistinguishable from the verifier’s view $\rm{View}_{V^{\ast}}[P(x, y) \leftrightarrow V^{\ast}(x)]$.

If the proof is zero knowledge, the adversary can simulate conversations on his own without knowing the secret. Meaning that the adversary learns nothing from the conversation.

How to give a formal proof for HVZK…? ↩︎