13. Sigma Protocols

The previous 3-coloring example certainly works as a zero knowledge proof, but is quite slow, and requires a lot of interaction. There are efficient protocols for interactive proofs, we will study sigma protocols.

Sigma Protocols

Definition

Definition. An effective relation is a binary relation $\mc{R} \subset \mc{X} \times \mc{Y}$, where $\mc{X}$, $\mc{Y}$, $\mc{R}$ are efficiently recognizable finite sets. Elements of $\mc{Y}$ are called statements. If $(x, y) \in \mc{R}$, then $x$ is called a witness for $y$.

Definition. Let $\mc{R} \subset \mc{X} \times \mc{Y}$ be an effective relation. A sigma protocol for $\mc{R}$ is a pair of algorithms $(P, V)$ satisfying the following.

- The prover $P$ is an interactive protocol algorithm, which takes $(x, y) \in \mc{R}$ as input.

- The verifier $V$ is an interactive protocol algorithm, which takes $y \in \mc{Y}$ as input, and outputs $\texttt{accept}$ or $\texttt{reject}$.

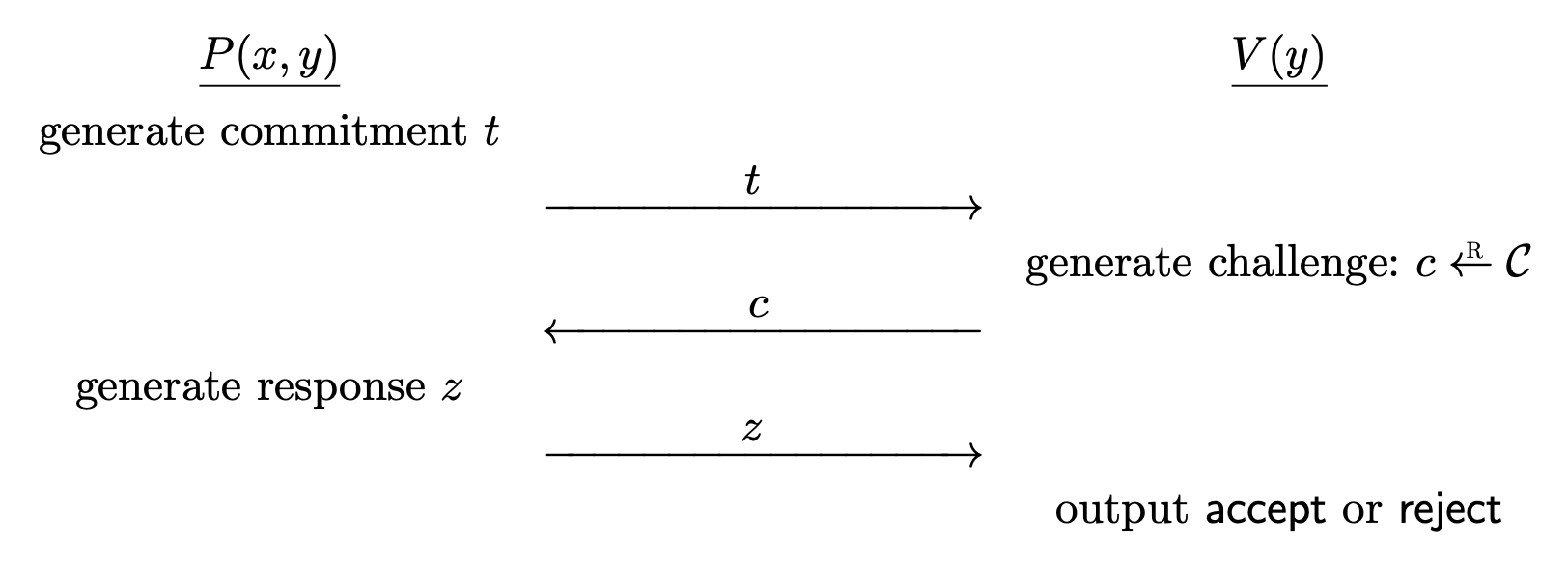

The interaction goes as follows.1

- $P$ computes a commitment message $t$ and sends it to $V$.

- $V$ chooses a random challenge $c \la \mc{C}$ from a challenge space and sends it to $P$.

- $P$ computes a response $z$ and sends it to $V$.

- $V$ outputs either $\texttt{accept}$ or $\texttt{reject}$, computed strictly as a function of the statement $y$ and the conversation $(t, c, z)$.

For all $(x, y) \in \mc{R}$, at the end of the interaction between $P(x, y)$ and $V(y)$, $V(y)$ always outputs $\texttt{accept}$.

- The verifier is deterministic except for choosing a random challenge $c \la \mc{C}$.

- If the output is $\texttt{accept}$, then the conversation $(t, c, z)$ is an accepting conversation for $y$.

- In most cases, the challenge space has to be super-poly. We say that the protocol has a large challenge space.

Soundness

The soundness property says that it is infeasible for any prover to make the verifier accept a statement that is false.

Definition. Let $\Pi = (P, V)$ be a sigma protocol for $\mc{R} \subset \mc{X}\times \mc{Y}$. For a given adversary $\mc{A}$, the security game goes as follows.

- The adversary chooses a statement $y^{\ast} \in \mc{Y}$ and gives it to the challenger.

- The adversary interacts with the verifier $V(y^{\ast})$, where the challenger plays the role of verifier, and the adversary is a possibly cheating prover.

The adversary wins if $V(y^{\ast})$ outputs $\texttt{accept}$ but $y^{\ast} \notin L_\mc{R}$. The advantage of $\mc{A}$ with respect to $\Pi$ is denoted $\rm{Adv}_{\rm{Snd}}[\mc{A}, \Pi]$ and defined as the probability that $\mc{A}$ wins the game.

If the advantage is negligible for all efficient adversaries $\mc{A}$, then $\Pi$ is sound.

Special Soundness

For sigma protocols, it suffices to require special soundness.

Definition. Let $(P, V)$ be a sigma protocol for $\mc{R} \subset \mc{X} \times \mc{Y}$. $(P, V)$ provides special soundness if there is an efficient deterministic algorithm $\rm{Ext}$, called a knowledge extractor with the following property.

Given a statement $y \in \mc{Y}$ and two accepting conversations $(t, c, z)$ and $(t, c’, z’)$ with $c \neq c’$, $\rm{Ext}$ outputs a witness (proof) $x \in \mc{X}$ such that $(x, y) \in \mc{R}$.

The extractor efficiently finds a proof $x$ for $y \in \mc{Y}$. This means, if a possibly cheating prover $P^{\ast}$ makes $V$ accept $y$ with non-negligible probability, then $P^{\ast}$ must have known a proof $x$ for $y$. Thus $P^{\ast}$ isn’t actually a dishonest prover, he already has a proof.

Note that the commitment $t$ is the same for the two accepting conversations. The challenge $c$ and $c’$ are chosen after the commitment, so if the prover can come up with $z$ and $z’$ so that $(t, c, z)$ and $(t, c’, z’)$ are accepting conversations for $y$, then the prover must have known $x$.

We also require that the challenge space is large, the challenger shouldn’t be accepted by luck.

Special Soundness $\implies$ Soundness

Theorem. Let $\Pi$ be a sigma protocol with a large challenge space. If $\Pi$ provides special soundness, then $\Pi$ is sound.

For every efficient adversary $\mc{A}$,

\[\rm{Adv}_{\rm{Snd}}[\mc{A}, \Pi] \leq \frac{1}{N}\]where $N$ is the size of the challenge space.

Proof. Suppose that $\mc{A}$ chooses a false statement $y^{\ast}$ and a commitment $t^{\ast}$. It suffices to show that there exists at most one challenge $c$ such that $(t^{\ast}, c, z)$ is an accepting conversation for some response $z$.

If there were two such challenges $c, c’$, then there would be two accepting conversations for $y^{\ast}$, which are $(t^{\ast}, c, z)$ and $(t^{\ast}, c’, z’)$. Now by special soundness, there exists a witness $x$ for $y^{\ast}$, which is a contradiction.

Special Honest Verifier Zero Knowledge

The conversation between $P$ and $V$ must not reveal anything.

Definition. Let $(P, V)$ be a sigma protocol for $\mc{R} \subset \mc{X} \times \mc{Y}$. $(P, V)$ is special honest verifier zero knowledge (special HVZK) if there exists an efficient probabilistic algorithm $\rm{Sim}$ (simulator) that satisfies the following.

- For all inputs $(y, c) \in \mc{Y} \times \mc{C}$, $\rm{Sim}(y, c)$ outputs a pair $(t, z)$ such that $(t, c, z)$ is always an accepting conversation for $y$.

- For all $(x, y) \in \mc{R}$, let $c \la \mc{C}$ and $(t, z) \la \rm{Sim}(y, c)$. Then $(t, c, z)$ has the same distribution as the conversation between $P(x, y)$ and $V(y)$.

The difference is that the simulator takes an additional input $c$. Also, the simulator produces an accepting conversation even if the statement $y$ does not have a proof.

Also note that the simulator is free to generate the messages in any convenient order.

The Schnorr Identification Protocol Revisited

The Schnorr identification protocol is actually a sigma protocol. Refer to Schnorr identification protocol (Modern Cryptography) for the full description.

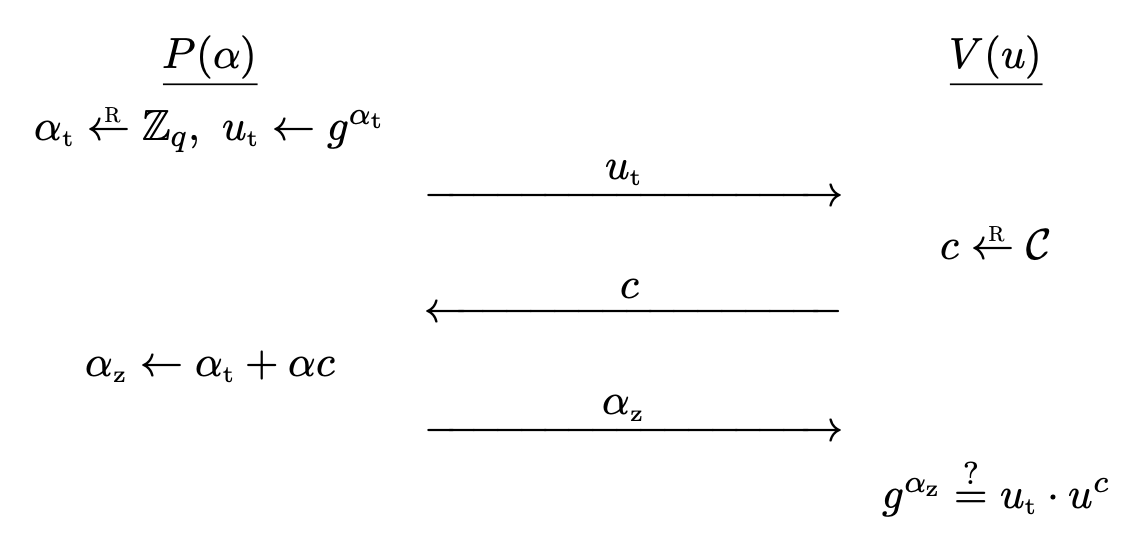

The pair $(P, V)$ is a sigma protocol for the relation $\mc{R} \subset \mc{X} \times \mc{Y}$ where

\[\mc{X} = \bb{Z}_q, \quad \mc{Y} = G, \quad \mc{R} = \left\lbrace (\alpha, u) \in \bb{Z}_q \times G : g^\alpha = u \right\rbrace.\]The challenge space $\mc{C}$ is a subset of $\bb{Z}_q$.

The protocol provides special soundness. If $(u_t, c, \alpha_z)$ and $(u_t, c’, \alpha_z’)$ are two accepting conversations with $c \neq c’$, then we have

\[g^{\alpha_z} = u_t \cdot u^c, \quad g^{\alpha_z'} = u_t \cdot u^{c'},\]so we have $g^{\alpha_z - \alpha_z’} = u^{c - c’}$. Setting $\alpha^{\ast} = (\alpha_z - \alpha_z’) /(c - c’)$ satisfies $g^{\alpha^{\ast}} = u$, solving the discrete logarithm and $\alpha^{\ast}$ is a proof.

As for HVZK, the simulator chooses $\alpha_z \la \bb{Z}_q$, $c \la \mc{C}$ randomly and sets $u_t = g^{\alpha_z} \cdot u^{-c}$. Then $(u_t, c, \alpha_z)$ will be accepted. Note that the order doesn’t matter. Also, the distribution is same, since $c$ and $\alpha_z$ are uniform over $\mc{C}$ and $\bb{Z}_q$ and the choice of $c$ and $\alpha_z$ determines $u_t$ uniquely. This is identical to the distribution in the actual protocol.

Dishonest Verifier

In case of dishonest verifiers, $V$ may not follow the protocol. For example, $V$ may choose non-uniform $c \in \mc{C}$ depending on the commitment $u_t$. In this case, the conversation from the actual protocol and the conversation generated by the simulator will have different distributions.

We need a different distribution. The simulator must also take the verifier’s actions as input, to properly simulate the dishonest verifier.

Modified Schnorr Protocol

The original protocol can be modified so that the challenge space $\mc{C}$ is smaller. Completeness property is obvious, and the soundness error grows, but we can always repeat the protocol.

As for zero knowledge, the simulator $\rm{Sim}_{V^{\ast}}(u)$ generates a verifier’s view $(u, c, z)$ as follows.

- Guess $c’ \la \mc{C}$. Sample $z’ \la \bb{Z}_q$ and set $u’ = g^{z’}\cdot u^{-c’}$. Send $u’$ to $V^{\ast}$.

- If the response from the verifier $V^{\ast}(u’)$ is $c$ and $c \neq c’$, restart.

- $c = c’$ holds with probability $1 / \left\lvert \mc{C} \right\lvert$, since $c’$ is uniform.

- Otherwise, output $(u, c, z) = (u’, c’, z’)$.

Sending $u’$ to $V^{\ast}$ is possible because the simulator also takes the actions of $V^{\ast}$ as input. The final output conversation has distribution identical to the real protocol execution.

Overall, this modified protocol works for dishonest verifiers, at the cost of efficiency because of the increased soundness error. We have a security-efficiency tradeoff.

But in most cases, it is enough to assume honest verifiers, as we will see soon.

Other Sigma Protocol Examples

Okamoto’s Protocol

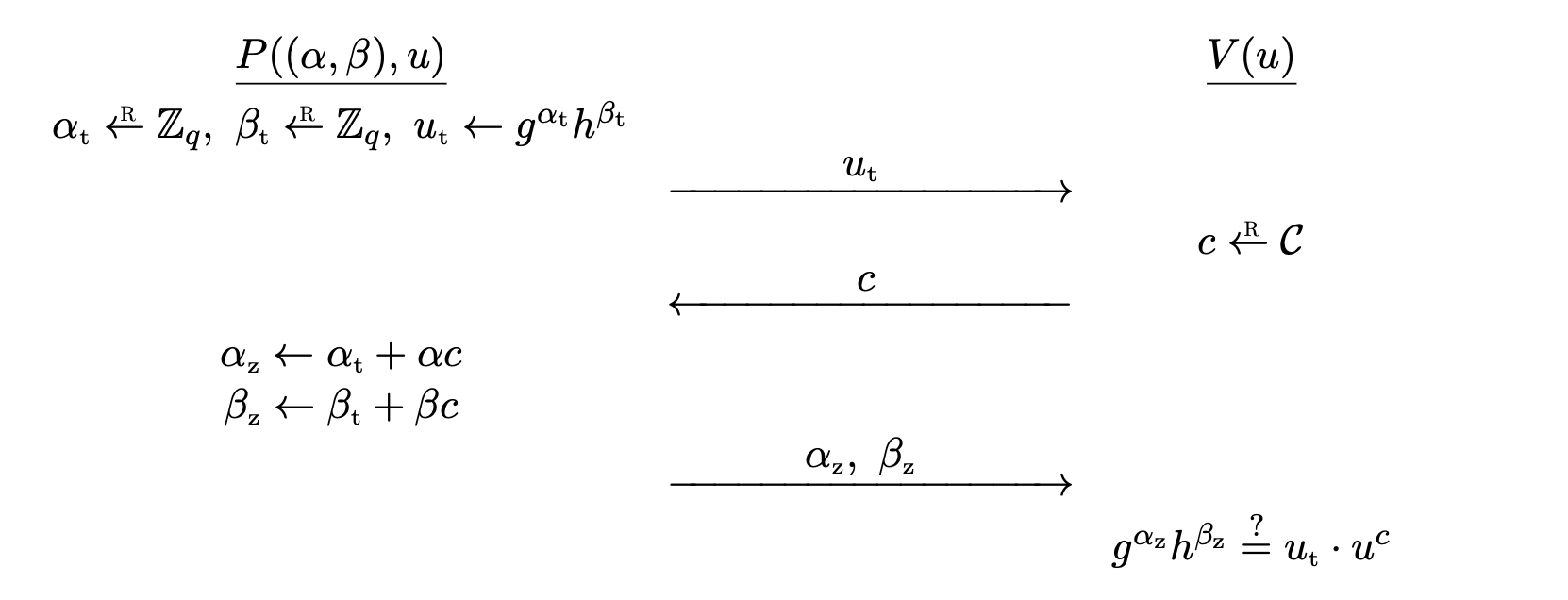

This one is similar to Schnorr protocol. This is used for proving the representation of a group element.

Let $G = \left\langle g \right\rangle$ be a cyclic group of prime order $q$, let $h \in G$ be some arbitrary group element, fixed as a system parameter. A representation of $u$ relative to $g$ and $h$ is a pair $(\alpha, \beta) \in \bb{Z}_q^2$ such that $g^\alpha h^\beta = u$.

Okamoto’s protocol for the relation

\[\mc{R} = \bigg\lbrace \big( (\alpha, \beta), u \big) \in \bb{Z}_q^2 \times G : g^\alpha h^\beta = u \bigg\rbrace\]goes as follows.

- $P$ computes random $\alpha_t, \beta_t \la \bb{Z}_q$ and sends commitment $u_t \la g^{\alpha_t}h^{\beta_t}$ to $V$.

- $V$ computes challenge $c \la \mc{C}$ and sends it to $P$.

- $P$ computes $\alpha_z \la \alpha_t + \alpha c$, $\beta_z \la \beta_t + \beta c$ and sends $(\alpha_z, \beta_z)$ to $V$.

- $V$ outputs $\texttt{accept}$ if and only if $g^{\alpha_z} h^{\beta_z} = u_t \cdot u^c$.

Completeness is obvious.

Theorem. Okamoto’s protocol provides special soundness and is special HVZK.

Proof. Very similar to the proof of Schnorr. Refer to Theorem 19.9.2

The Chaum-Pedersen Protocol for DH-Triples

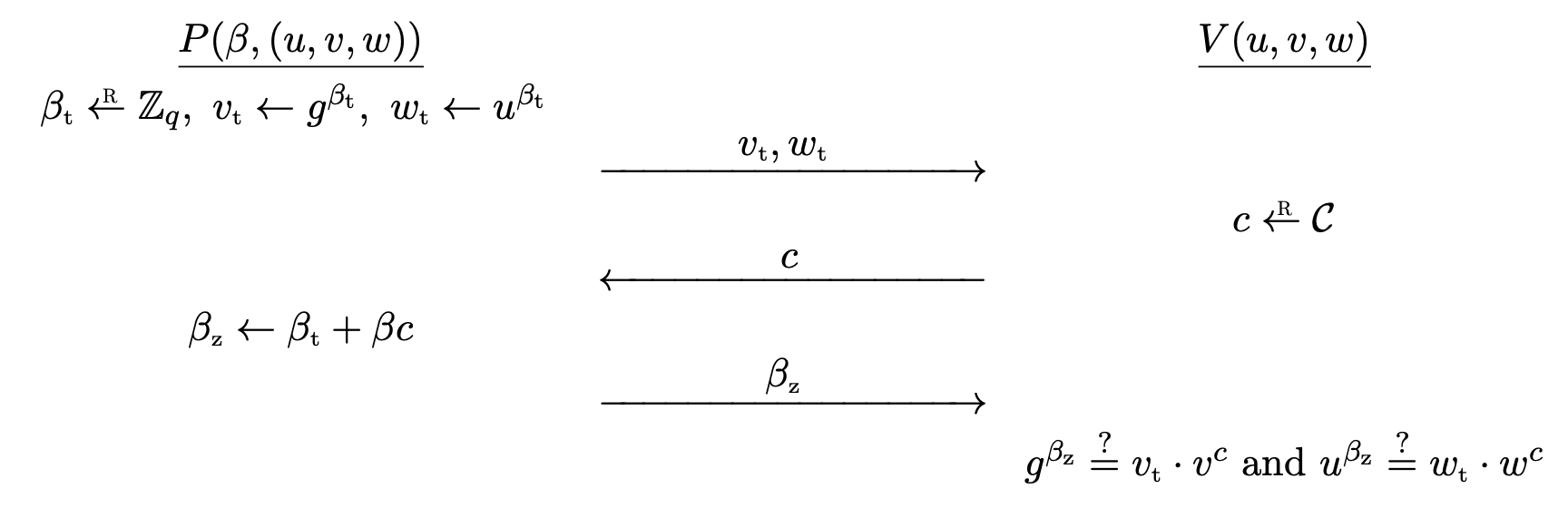

The Chaum-Pederson protocol is for convincing a verifier that a given triple is a DH-triple.

Let $G = \left\langle g \right\rangle$ be a cyclic group of prime order $q$. $(g^\alpha, g^\beta, g^\gamma)$ is a DH-triple if $\gamma = \alpha\beta$. Then, the triple $(u, v, w)$ is a DH-triple if and only if $v = g^\beta$ and $w = u^\beta$ for some $\beta \in \bb{Z}_q$.

The Chaum-Pederson protocol for the relation

\[\mc{R} = \bigg\lbrace \big( \beta, (u, v, w) \big) \in \bb{Z}_q \times G^3 : v = g^\beta \land w = u^\beta \bigg\rbrace\]goes as follows.

- $P$ computes random $\beta_t \la \bb{Z}_q$ and sends commitment $v_t \la g^{\beta_t}$, $w_t \la u^{\beta_t}$ to $V$.

- $V$ computes challenge $c \la \mc{C}$ and sends it to $P$.

- $P$ computes $\beta_z \la \beta_t + \beta c$, and sends it to $V$.

- $V$ outputs $\texttt{accept}$ if and only if $g^{\beta_z} = v_t \cdot v^c$ and $u^{\beta_z} = w_t \cdot w^c$.

Completeness is obvious.

Theorem. The Chaum-Pedersen protocol provides special soundness and is special HVZK.

Proof. Also similar. See Theorem 19.10.2

This can be used to prove that an ElGamal ciphertext $c = (u, v) = (g^k, h^k \cdot m)$ is an encryption of $m$ with public key $h = g^\alpha$, without revealing the private key or the ephemeral key $k$. If $(g^k, h^k \cdot m)$ is a valid ciphertext, then $(h, u, vm^{-1}) = (g^\alpha, g^k, g^{\alpha k})$ is a valid DH-triple.

Sigma Protocol for Arbitrary Linear Relations

Schnorr, Okamoto, Chaum-Pedersen protocols look similar. They are special cases of a generic sigma protocol for proving a linear relation among group elements. Read more in Section 19.5.3.2

Sigma Protocol for RSA

Let $(n, e)$ be an RSA public key, where $e$ is prime. The Guillou-Quisquater (GQ) protocol is used to convince a verifier that he knows an $e$-th root of $y \in \bb{Z}_n^{\ast}$.

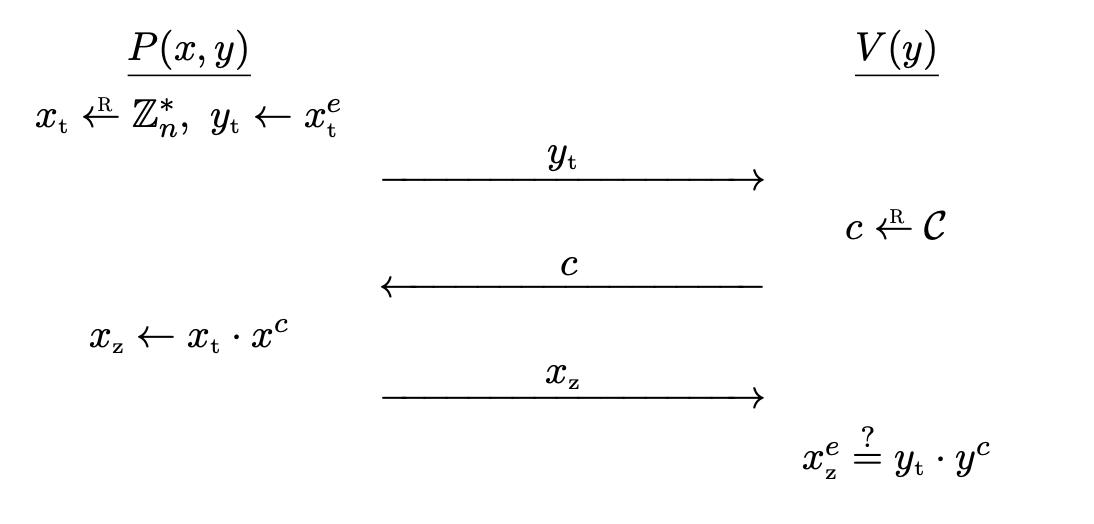

The Guillou-Quisquater protocol for the relation

\[\mc{R} = \bigg\lbrace (x, y) \in \big( \bb{Z}_n^{\ast} \big)^2 : x^e = y \bigg\rbrace\]goes as follows.

- $P$ computes random $x_t \la \bb{Z}_n^{\ast}$ and sends commitment $y_t \la x_t^e$ to $V$.

- $V$ computes challenge $c \la \mc{C}$ and sends it to $P$.

- $P$ computes $x_z \la x_t \cdot x^c$ and sends it to $V$.

- $V$ outputs $\texttt{accept}$ if and only if $x_z^e = y_t \cdot y^c$.

Completeness is obvious.

Theorem. The GQ protocol provides special soundness and is special HVZK.

Proof. Also similar. See Theorem 19.13.2

Combining Sigma Protocols

Using the basic sigma protocols, we can build sigma protocols for complex statements.

AND-Proof Construction

The construction is straightforward, since we can just prove both statements.

Given two sigma protocols $(P_0, V_0)$ for $\mc{R}0 \subset \mc{X}_0 \times \mc{Y}_0$ and $(P_1, V_1)$ for $\mc{R}_1 \subset \mc{X}_1 \times \mc{Y}_1$, we construct a sigma protocol for the relation $\mc{R}\rm{AND}$ defined on $(\mc{X}_0 \times \mc{X}_1) \times (\mc{Y}_0 \times \mc{Y}_1)$ as

\[\mc{R}_\rm{AND} = \bigg\lbrace \big( (x_0, x_1), (y_0, y_1) \big) : (x_0, y_0) \in \mc{R}_0 \land (x_1, y_1) \in \mc{R}_1 \bigg\rbrace.\]Given a pair of statements $(y_0, y_1) \in \mc{Y}_0 \times \mc{Y}_1$, the prover tries to convince the verifier that he knows a proof $(x_0, x_1) \in \mc{X}_0 \times \mc{X}_1$. This is equivalent to proving the AND of both statements.

- $P$ runs $P_i(x_i, y_i)$ to get a commitment $t_i$. $(t_0, t_1)$ is sent to $V$.

- $V$ computes challenge $c \la C$ and sends it to $P$.

- $P$ uses the challenge for both $P_0, P_1$, obtains response $z_0$, $z_1$, which is sent to $V$.

- $V$ outputs $\texttt{accept}$ if and only if $(t_i, c, z_i)$ is an accepting conversation for $y_i$.

Completeness is clear.

Theorem. If $(P_0, V_0)$ and $(P_1, V_1)$ provide special soundness and are special HVZK, then the AND protocol $(P, V)$ defined above also provides special soundness and is special HVZK.

Proof. For special soundness, let $\rm{Ext}_0$, $\rm{Ext}_1$ be the knowledge extractor for $(P_0, V_0)$ and $(P_1, V_1)$, respectively. Then the knowledge extractor $\rm{Ext}$ for $(P, V)$ can be constructed straightforward. For statements $(y_0, y_1)$, suppose that $\big( (t_0, t_1), c, (z_0, z_1) \big)$ and $\big( (t_0, t_1), c’, (z_0’, z_1’) \big)$ are two accepting conversations. Feed $\big( y_0, (t_0, c, z_0), (t_0, c’, z_0’) \big)$ to $\rm{Ext}_0$, and feed $\big( y_1, (t_1, c, z_1), (t_1, c’, z_1’) \big)$ to $\rm{Ext}_1$.

For special HVZK, let $\rm{Sim}_0$ and $\rm{Sim}_1$ be simulators for each protocol. Then the simulator $\rm{Sim}$ for $(P, V)$ is built by using $(t_0, z_0) \la \rm{Sim}_0(y_0, c)$ and $(t_1, z_1) \la \rm{Sim}_1(y_1, c)$. Set

\[\big( (t_0, t_1), (z_0, z_1) \big) \la \rm{Sim}\big( (y_0, y_1), c \big).\]We have used the fact that the challenge is used for both protocols.

OR-Proof Construction

However, OR-proof construction is difficult. The prover must convince the verifier that either one of the statement is true, but should not reveal which one is true.

If the challenge is known in advance, the prover can cheat. We exploit this fact. For the proof of $y_0 \lor y_1$, do the real proof for $y_b$ and cheat for $y_{1-b}$.

Suppose we are given two sigma protocols $(P_0, V_0)$ for $\mc{R}_0 \subset \mc{X}_0 \times \mc{Y}_0$ and $(P_1, V_1)$ for $\mc{R}_1 \subset \mc{X}_1 \times \mc{Y}_1$. We assume that these both use the same challenge space, and both are special HVZK with simulators $\rm{Sim}_0$ and $\rm{Sim}_1$.

We combine the protocols to form a sigma protocol for the relation $\mc{R}_\rm{OR}$ defined on ${} \big( \braces{0, 1} \times (\mc{X}_0 \cup \mc{X}_1) \big) \times (\mc{Y}_0\times \mc{Y}_1) {}$ as

\[\mc{R}_\rm{OR} = \bigg\lbrace \big( (b, x), (y_0, y_1) \big): (x, y_b) \in \mc{R}_b\bigg\rbrace.\]Here, $b$ denotes the actual statement $y_b$ to prove. For $y_{1-b}$, we cheat.

$P$ is initialized with $\big( (b, x), (y_0, y_1) \big) \in \mc{R}_\rm{OR}$ and $V$ is initialized with $(y_0, y_1) \in \mc{Y}_0 \times \mc{Y}_1$. Let $d = 1 - b$.

- $P$ computes $c_d \la \mc{C}$ and $(t_d, z_d) \la \rm{Sim}_d(y_d, c_d)$.

- $P$ runs $P_b(x, y_b)$ to get a real commitment $t_b$ and sends $(t_0, t_1)$ to $V$.

- $V$ computes challenge $c \la C$ and sends it to $P$.

- $P$ computes $c_b \la c \oplus c_d$, feeds it to $P_b(x, y_b)$ obtains a response $z_b$.

- $P$ sends $(c_0, z_0, z_1)$ to $V$.

- $V$ computes $c_1 \la c \oplus c_0$, and outputs $\texttt{accept}$ if and only if $(t_0, c_0, z_0)$ is an accepting conversation for $y_0$ and $(t_1, c_1, z_1)$ is an accepting conversation for $y_1$.

Step $1$ is the cheating part, where the prover chooses a challenge, and generates a commitment and a response from the simulator.

Completeness follows from the following.

- $c_b = c \oplus c_{1-b}$, so $c_1 = c \oplus c_0$ always holds.

- Both conversations $(t_0, c_0, z_0)$ and $(t_1, c_1, z_1)$ are accepted.

- An actual proof is done for statement $y_b$.

- For statement $y_{1-b}$, the simulator always outputs an accepting conversation.

$c_b = c \oplus c_d$ is random, so $P$ cannot manipulate the challenge. Also, $V$ checks $c_1 = c \oplus c_0$.

Theorem. If $(P_0, V_0)$ and $(P_1, V_1)$ provide special soundness and are special HVZK, then the OR protocol $(P, V)$ defined above also provides special soundness and is special HVZK.

Proof. For special soundness, suppose that $\rm{Ext}_0$ and $\rm{Ext}_1$ are knowledge extractors. Let

\[\big( (t_0, t_1), c, (c_0, z_0, z_1) \big), \qquad \big( (t_0, t_1), c', (c_0', z_0', z_1') \big)\]be two accepting conversations with $c \neq c’$. Define $c_1 = c \oplus c_0$ and $c_1’ = c’ \oplus c_0’$. Since $c \neq c’$, it must be the case that either $c_0 \neq c_0’$ or $c_1 \neq c_1’$. Now $\rm{Ext}$ will work as follows.

- If $c_0 \neq c_0’$, output $\bigg( 0, \rm{Ext}_0\big( y_0, (t_0, c_0, z_0), (t_0, c_0’, z_0’) \big) \bigg)$.

- If $c_1 \neq c_1’$, output $\bigg( 1, \rm{Ext}_1\big( y_1, (t_1, c_1, z_1), (t_1, c_1’, z_1’) \big) \bigg)$.

Then $\rm{Ext}$ will extract the knowledge.

For special HVZK, define $c_0 \la \mc{C}$, $c_1 \la c \oplus c_0$. Then run each simulator to get

\[(t_0, z_0) \la \rm{Sim}_0(y_0, c_0), \quad (t_1, z_1) \la \rm{Sim}_1(y_1, c_1).\]Then the simulator for $(P, V)$ outputs

\[\big( (t_0, t_1), (c_0, z_0, z_1) \big) \la \rm{Sim}\big( (y_0, y_1), c \big).\]The simulator just simulates for both of the statements and returns the messages as in the protocol. $c_b$ is random, and the remaining values have the same distribution since the original two protocols were special HVZK.

Example: OR of Sigma Protocols with Schnorr Protocol

Let $G = \left\langle g \right\rangle$ be a cyclic group of prime order $q$. The prover wants to convince the verifier that he knows the discrete logarithm of either $h_0$ or $h_1$ in $G$.

Suppose that the prover knows $x_b \in \bb{Z}_q$ such that $g^{x_b} = h_b$.

- Choose $c_{1-b} \la \mc{C}$ and call simulator of $1-b$ to obtain $(u_{1-b}, z_{1-b}) \la \rm{Sim}_{1-b}$.

- $P$ sends two commitments $u_0, u_1$.

- For $u_b$, choose random $y \la \bb{Z}_q$ and set $u_b = g^y$.

- For $u_{1-b}$, use the value from the simulator.

- $V$ sends a single challenge $c \la \mc{C}$.

- Using $c_{1-b}$, split the challenge into $c_0$, $c_1$ so that they satisfy $c_0 \oplus c_1 = c$. Then send $(c_0, c_1, z_0, z_1)$ to $V$.

- For $z_b$, calculate $z_b \la y + c_b x$.

- For $z_{1-b}$, use the value from the simulator.

- $V$ checks if $c = c_0 \oplus c_1$. $V$ accepts if and only if $(u_0, c_0, z_0)$ and $(u_1, c_1, z_1)$ are both accepting conversations.

- Since $c, c_{1-b}$ are random, $c_b$ is random. Thus one of the proofs must be valid.

Generalized Constructions

See Exercise 19.26 and 19.28.2

Non-interactive Proof Systems

Sigma protocols are interactive proof systems, but we can convert them into non-interactive proof systems using the Fiat-Shamir transform.

First, the definition of non-interactive proof systems.

Definition. Let $\mc{R} \subset \mc{X} \times \mc{Y}$ be an effective relation. A non-interactive proof system for $\mc{R}$ is a pair of algorithms $(G, V)$ satisfying the following.

- $G$ is an efficient probabilistic algorithm that generates the proof as $\pi \la G(x, y)$ for $(x, y) \in \mc{R}$. $\pi$ belongs to some proof space $\mc{PS}$.

- $V$ is an efficient deterministic algorithm that verifies the proof as $V(y, \pi)$ where $y \in \mc{Y}$ and $\pi \in \mc{PS}$. $V$ outputs either $\texttt{accept}$ or $\texttt{reject}$. If $V$ outputs $\texttt{accept}$, $\pi$ is a valid proof for $y$.

For all $(x, y) \in \mc{R}$, the output of $G(x, y)$ must be a valid proof for $y$.

Non-interactive Soundness

Intuitively, it is hard to create a valid proof of a false statement.

Definition. Let $\Phi = (G, V)$ be a non-interactive proof system for $\mc{R} \subset \mc{X} \times \mc{Y}$ with proof space $\mc{PS}$. An adversary $\mc{A}$ outputs a statement $y^{\ast} \in \mc{Y}$ and a proof $\pi^{\ast} \in \mc{PS}$ to attack $\Phi$.

The adversary wins if $V(y^{\ast}, \pi^{\ast}) = \texttt{accept}$ and $y^{\ast} \notin L_\mc{R}$. The advantage of $\mc{A}$ with respect to $\Phi$ is defined as the probability that $\mc{A}$ wins, and is denoted as $\rm{Adv}_{\rm{niSnd}}[\mc{A}, \Phi]$.

If the advantage is negligible for all efficient adversaries $\mc{A}$, $\Phi$ is sound.

Non-interactive Zero Knowledge

Omitted.

The Fiat-Shamir Transform

The basic idea is using a hash function to derive a challenge, instead of a verifier. Now the only job of the verifier is checking the proof, requiring no interaction for the proof.

Definition. Let $\Pi = (P, V)$ be a sigma protocol for a relation $\mc{R} \subset \mc{X} \times \mc{Y}$. Suppose that conversations $(t, c, z) \in \mc{T} \times \mc{C} \times \mc{Z}$. Let $H : \mc{Y} \times \mc{T} \rightarrow \mc{C}$ be a hash function.

Define the Fiat-Shamir non-interactive proof system $\Pi_\rm{FS} = (G_\rm{FS}, V_\rm{FS})$ with proof space $\mc{PS} = \mc{T} \times \mc{Z}$ as follows.

- For input $(x, y) \in \mc{R}$, $G_\rm{FS}$ runs $P(x, y)$ to obtain a commitment $t \in \mc{T}$. Then computes the challenge $c = H(y, t)$, which is fed to $P(x, y)$, obtaining a response $z \in \mc{Z}$. $G_\rm{FS}$ outputs $(t, z) \in \mc{T} \times \mc{Z}$.

- For input $\big( y, (t, z) \big) \in \mc{Y} \times (\mc{T} \times \mc{Z})$, $V_\rm{FS}$ verifies that $(t, c, z)$ is an accepting conversation for $y$, where $c = H(y, t)$.

Any sigma protocol can be converted into a non-interactive proof system. Its completeness is automatically given by the completeness of the sigma protocol.

By modeling the hash function as a random oracle, we can show that:

- If the sigma protocol is sound, then so is the non-interactive proof system.3

- If the sigma protocol is special HVZK, then running the non-interactive proof system does not reveal any information about the secret.

Implications

- No interactions are required, resulting in efficient protocols with lower round complexity.

- No need to consider dishonest verifiers, since prover chooses the challenge. The verifier only verifies.

- In distributed systems, a single proof can be used multiple times.

Soundness of the Fiat-Shamir Transform

Theorem. Let $\Pi$ be a sigma protocol for a relation $\mc{R} \subset \mc{X} \times \mc{Y}$, and let $\Pi_\rm{FS}$ be the Fiat-Shamir non-interactive proof system derived from $\Pi$ with hash function $H$. If $\Pi$ is sound and $H$ is modeled as a random oracle, then $\Pi_\rm{FS}$ is also sound.

Let $\mc{A}$ be a $q$-query adversary attacking the soundness of $\Pi_\rm{FS}$. There exists an adversary $\mc{B}$ attacking the soundness of $\Pi$ such that

\[\rm{Adv}_{\rm{niSnd^{ro}}}[\mc{A}, \Pi_\rm{FS}] \leq (q + 1) \rm{Adv}_{\rm{Snd}}[\mc{B}, \Pi].\]

Proof Idea. Suppose that $\mc{A}$ produces a valid proof $(t^{\ast}, z^{\ast})$ on a false statement $y^{\ast}$. Without loss of generality, $\mc{A}$ queries the random oracle at $(y^{\ast}, t^{\ast})$ within $q+1$ queries. Then $\mc{B}$ guesses which of the $q+1$ queries is the relevant one. If $\mc{B}$ guesses the correct query, the conversation $(t^{\ast}, c, z^{\ast})$ will be accepted and $\mc{B}$ succeeds. The factor $q+1$ comes from the choice of $\mc{B}$.

Zero Knowledge of the Fiat-Shamir Transform

Omitted. Works…

The Fiat-Shamir Signature Scheme

Now we understand why the Schnorr signature scheme used hash functions. In general, the Fiat-Shamir transform can be used to convert sigma protocols into signature schemes.

We need $3$ building blocks.

- A sigma protocol $(P, V)$ with conversations of the form $(t, c, z)$.

- A key generation algorithm $G$ for $\mc{R}$, that outputs $pk = y$, $sk = (x, y) \in \mc{R}$.

- A hash function $H : \mc{M} \times \mc{T} \rightarrow \mc{C}$, modeled as a random oracle.

Definition. The Fiat-Shamir signature scheme derived from $G$ and $(P, V)$ works as follows.

- Key generation: invoke $G$ so that $(pk, sk) \la G()$.

- $pk = y \in \mc{Y}$ and $sk = (x, y) \in \mc{R}$.

- Sign: for message $m \in \mc{M}$

- Start the prover $P(x, y)$ and obtain the commitment $t \in \mc{T}$.

- Compute the challenge $c \la H(m, t)$.

- $c$ is fed to the prover, which outputs a response $z$.

- Output the signature $\sigma = (t, z) \in \mc{T} \times \mc{Z}$.

- Verify: with the public key $pk = y$, compute $c \la H(m, t)$ and check that $(t, c, z)$ is an accepting conversation for $y$ using $V(y)$.

If an adversary can come up with a forgery, then the underlying sigma protocol is not secure.

Example: Voting Protocol

$n$ voters are casting a vote, either $0$ or $1$. At the end, all voters learn the sum of the votes, but we want to keep the votes secret for each party.

We can use the multiplicative ElGamal encryption scheme in this case. Assume that a trusted vote tallying center generates a key pair, keeps $sk = \alpha$ to itself and publishes $pk = g^\alpha$.

Each voter encrypts the vote $b_i$ and the ciphertext is

\[(u_i, v_i) = (g^{\beta_i}, h^{\beta_i} \cdot g^{b_i})\]where $\beta_i \la\bb{Z}_q$. The vote tallying center aggregates all ciphertexts my multiplying everything. No need to decrypt yet. Then

\[(u^{\ast}, v^{\ast}) = \left( \prod_{i=1}^n g^{\beta_i}, \prod_{i=1}^n h^{\beta_i} \cdot g^{b_i} \right) = \big( g^{\beta^{\ast}}, h^{\beta^{\ast}} \cdot g^{b^{\ast}} \big),\]where $\beta^{\ast} = \sum_{i=1}^n \beta_i$ and $b^{\ast} = \sum_{i=1}^n b_i$. Now decrypt $(u^{\ast}, v^{\ast})$ and publish the result $b^{\ast}$.4

Since the ElGamal scheme is semantically secure, the protocol is also secure if all voters follow the protocol. But a dishonest voter can encrypt $b_i = -100$ or some arbitrary value.

To fix this, we can make each voter prove that the vote is valid. Using the Chaum-Pedersen protocol for DH-triples and the OR-proof construction, the voter can submit a proof that the ciphertext is either a encryption of $b_i = 0$ or $1$. We can also apply the Fiat-Shamir transform here for efficient protocols, resulting in non-interactive proofs.

The message flows in a shape that resembles the greek letter $\Sigma$, hence the name sigma protocol. ↩︎

A Graduate Course in Applied Cryptography. ↩︎ ↩︎2 ↩︎3 ↩︎4 ↩︎5

The challenge is chosen after the commitment, making it random. ↩︎

To find $b^{\ast}$, one has to solve the discrete logarithm, but for realistic $n$, we can brute force this. ↩︎