03. Symmetric Key Cryptography (2)

Block Cipher Overview

- We need confusion and diffusion

- Confusion: relationship between ciphertext and key is complex

- Diffusion: relationship between message and ciphertext is complex

- Series of substitutions and permutations can achieve confusion and diffusion

Modules

- S-box: a substitution module

- Usually for confusion, also gives diffusion

- $m \times n$ lookup box is used for implementation

- P-box: a permutation module

- Usually for diffusion

- Compared to the number of input bits,

- Expansion if the number of output bits is larger

- Compression if the number of output bits is smaller

- Straight if the number of output bits is equal

Data Encryption Standard (DES)

- Standardized in 1979.

- Block size is $64$ bits ($8$ bytes)

- $64$ bits input $\rightarrow$ $64$ bits output

- Key is $56$ bits, and every $8$th bit is a parity bit.

- Thus $64$ bits in total

Encryption

- From the $56$-bit key, generate $16$ different $48$ bit keys $k_1, \dots, k_{16}$.

- The plaintext message goes through an initial permutation.

- The output goes through $16$ rounds, and key $k_i$ is used in round $i$.

- After $16$ rounds, split the output into two $32$ bit halves and swap them.

- The output goes through the inverse of the permutation from Step 1.

Let $L_{i-1} \parallel R_{i-1}$ be the output of round $i-1$, where $L_{i-1}$ and $R_{i-1}$ are $32$ bit halves. Also let $f$ be the Feistel function.1

In each round $i$, the following operation is performed:

\[L_i = R_{i - 1}, \qquad R_i = L_{i-1} \oplus f(k_i, R_{i-1}).\]The Feistel Function

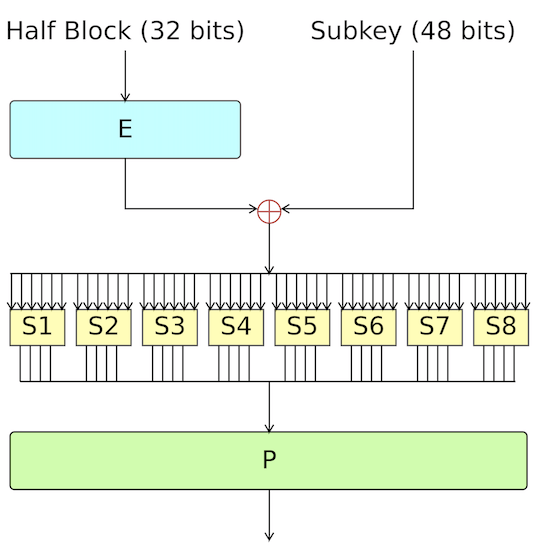

The Feistel function takes $32$ bit data and divides it into eight $4$ bit chunks. Each chunk is expanded to $6$ bits using a P-box. Now, we have 48 bits of data, so apply XOR with the key for this round. Next, each $6$-bit block is compressed back to $4$ bits using a S-box. Finally, there is a (straight) permutation at the end, resulting in $32$ bit data.

The Feistel function is not invertible.

Questions

- Why does the input go through the P-box and its inverse at the end?

- Not for security, but for efficient hardware design.

- Why do we swap each $32$ bit halves?

- Not for security, but for engineering purposes, see below.

- Is DES invertible?

- Yes, message should be decrypted.

- But the Feistel function is not invertible, since it sends $4$ bits to $6$ bits during the evaluation process. Then how is decryption possible?

Decryption

Let $f$ be the Feistel function. We can define each round as a function $F$,

\[F(L_i \parallel R_i) = R_i \parallel L_i \oplus f(R_i).\]Consider a function $G$, defined as

\[G(L_i \parallel R_i) = R_i \oplus f(L_i) \parallel L_i.\]Then, we see that

\[\begin{align*} G(F(L_i \parallel R_i)) &= G(R_i \parallel L_i \oplus f(R_i)) \\ &= (L_i \oplus f(R_i)) \oplus f(R_i) \parallel R_i \\ &= L_i \parallel R_i. \end{align*}\]Thus $F$ and $G$ are inverses of each other, thus $f$ doesn’t have to be invertible. This is called the Feistel cipher.

Also, note that

\[G(L_i \parallel R_i) = F(L_i \oplus f(R_i) \parallel R_i).\]Notice that evaluating $G$ is equivalent to evaluating $F$ on a encrypted block, with their upper/lower $32$ bit halves swapped. We get $L_i \oplus f(R_i) \parallel R_i$ exactly when we swap each halves of $F(L_i \parallel R_i)$. Thus, we can use the same hardware for encryption and decryption, which is the reason for swapping each $32$ bit halves.

Advanced Encryption Standard (AES)

- DES key only had $56$ bits, so DES was broken in the 1990s

- NIST standardized AES in 2001, based on Rijndael cipher

- AES has $3$ different key lengths: $128$, $192$, $256$

- Different number of rounds for different key lengths

- $10$, $12$, $14$ rounds respectively

- Input data block is $128$ bits, so viewed as $4\times 4$ table of bytes

- This table is called the current state

Each round consists of the following:

- SubBytes: byte substitution, 1 S-box on every byte

- ShiftRows: permutes bytes between groups and columns

- MixColumns: mix columns by using matrix multiplication in $\mathrm{GF}(2^8)$.

- AddRoundKey: XOR with round key

The first and last rounds are a little different.

- AddRoundKey is done before the first round.

- The last round does not have MixColumns.

The objectives of AES:

- Build resistance against known attacks

- Code must be compact, and should run fast on many CPUs

- Design must be simple

Layers

SubBytes

- A simple substitution of each byte using $16 \times 16$ lookup table.

- Each byte is split into two $4$ bit nibbles

- Left half is used as row index

- Right half is used as column index

ShiftRows

- A circular bytes shift for each row, so it is a permutation

- $i$-th row is shifted $i$ times to the left. ($i = 0, 1, 2, 3$)

MixColumns

- For each column, each byte is replaced by a value

- The value depends on all 4 bytes of the column

- Each column is processed separately

- Thus effectively, it is a matrix multiplication (Hill cipher).2

AddRoundKey

- XOR the input with $128$ bits of the round key

- The round key is different for each round

These 4 modules are all invertible!

Questions

- Why is there a AddRoundKey at the beginning?

- Why is the last round different?

Both are for engineering purposes, to make the encryption and decryption process the same.3

Modes of Operations

AES, DES use fixed block size for encryption. How do we encrypt longer messages? For long messages, there are many different ways to process each block of the message. This is called the mode of operation. We will look at 5 different modes of operations.

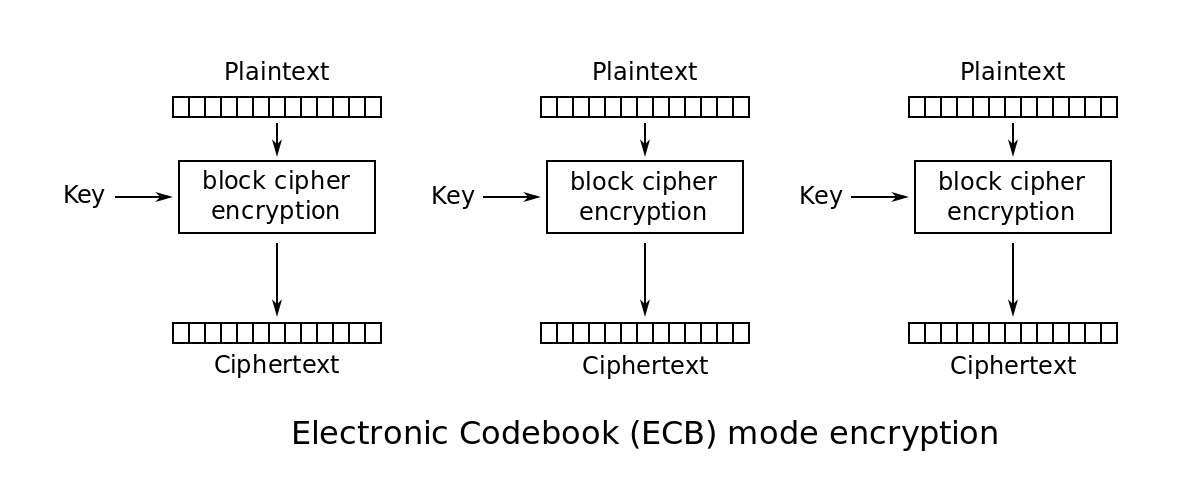

Electronic Codebook Mode (ECB)

- Codebook is a mapping table.

- For the $i$-th plaintext block, we use key $k$ to encrypt and obtain the $i$-th ciphertext block.

- Uses the same key for all blocks

- Adjacent blocks are independent of each other.

- Advantages

- Fast when run in parallel

- Limitations

- Repetitions in messages (if aligned with the block) may lead to repetitions in the ciphertext

- Susceptible to cut-and-paste attacks

- Mainly used to send a few blocks data

Cut-and-Paste Attack

Since the same key is used for all blocks, once a mapping from plaintext to ciphertext is known, a sequence of ciphertext blocks can be easily manipulated. The assumption here is that the encryption keys do not change frequently. So the attacker can cut some block from a ciphertext and paste it to manipulate the data. This is a chosen ciphertext attack.

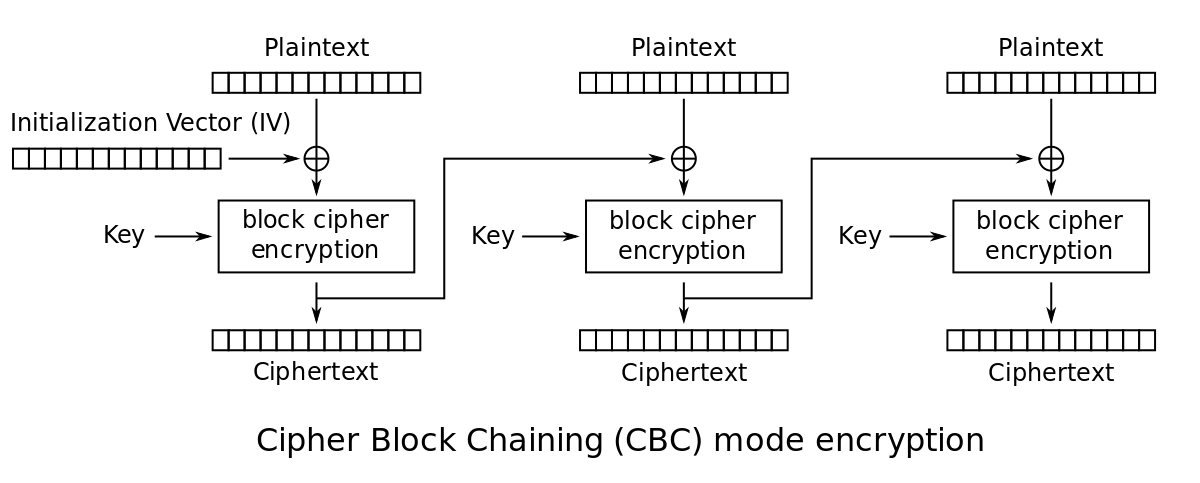

Cipher Block Chaining Mode (CBC)

- Two identical messages produce to different ciphertexts.

- This prevents chosen plaintext attacks

- Blocks are linked together in the encryption process

- Each previous cipher block is chained with current block

- Initialization vector is used

- Encryption

- Let $c_0$ be the initialization vector.

- $c_i = E(k, p_i \oplus c_{i - 1})$, where $p_i$ is the $i$-th plaintext block.

- The ciphertext is $(c_0, c_1, \dots)$.

- Decryption

- The first block $c_0$ contains the initialization vector.

- $p_i = c_{i - 1} \oplus D(k, c_i)$.

- The plaintext is $(p_1, p_2, \dots)$.

- Used for bulk data encryption, authentication

- Advantages

- Parallelism in decryption.

- Chosen plaintext attacks can be mitigated through randomized IV.

- Limitations

- Encryption is not parallelizable. Each ciphertext block depends on all previous blocks.

- Side note: CBC can be used to check message integrity. (MAC)

Error Propagation in CBC

- If there is a 1-bit error in the plaintext, then that error will affect that block and all the other blocks afterwards.

- This error doesn’t occur frequently since we are in the same system.

- If there is a 1-bit error in the ciphertext, then that error will affect only two blocks.

- This error can happen in transit through the network.

- CBC mode is self-recovering

Initialization Vector in CBC

- If the IV is the same, then the encryption of the same plaintext is the same.

- Thus IVs should be random.

- IV are not required to be secret, but

- No IVs should be reused under the same key

- IV changes should be unpredictable

- On IV reuse, same message will generate the same ciphertext if key isn’t changed

- If IV is predictable, CBC is vulnerable to chosen plaintext attacks.

- Define Eve’s new message $m’ = \mathrm{IV} _ {\mathrm{E}} \oplus \mathrm{IV} _ {\mathrm{A}} \oplus g$, where

- $\mathrm{IV} _ \mathrm{A}$ and $\mathrm{IV} _ \mathrm{E}$ are Alice and Eve’s IVs

- $g$ is a guess of Alice’s original message $m$.

- Since Eve can encrypt any message, $m’$ can be encrypted.

- $c’ = E _ k(\mathrm{IV} _ \mathrm{E} \oplus m’) = E _ k(\mathrm{IV} _ \mathrm{A} \oplus g)$.

- Then Eve can compare $c’$ and the original $c = E _ k(\mathrm{IV} _ \mathrm{A} \oplus m)$ to recover $m$.

- Useful when there are not many cases for $m$ (or most of the message is already known).

- Define Eve’s new message $m’ = \mathrm{IV} _ {\mathrm{E}} \oplus \mathrm{IV} _ {\mathrm{A}} \oplus g$, where

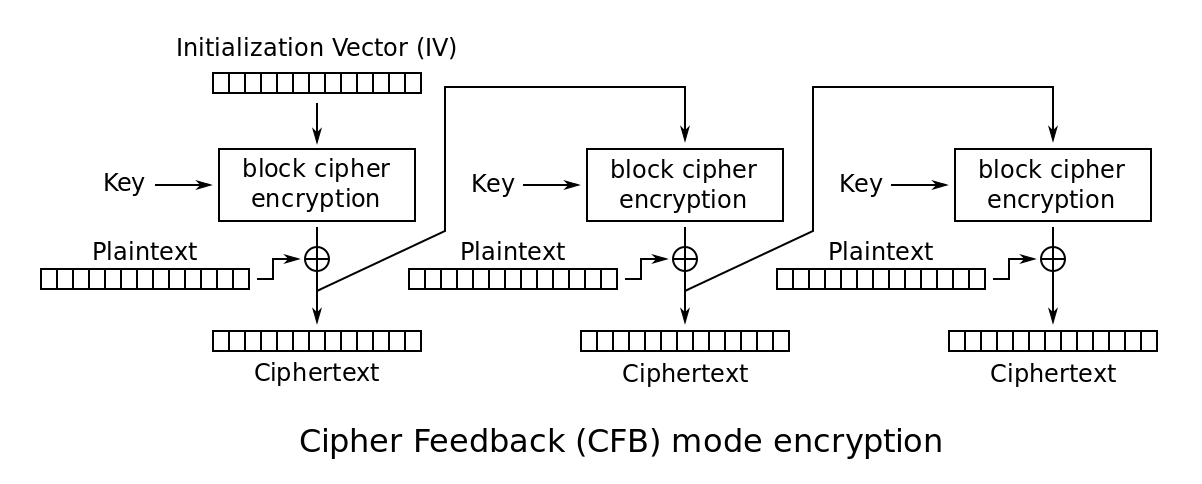

Cipher Feedback Mode (CFB)

- The message is treated as a stream of bits; similar to stream cipher

- Result of the encryption is fed to the next stage.

- Standard allows any number of bits to be fed to the next stage

- It is most efficient to use all bits.

- Initialization vector is used.

- Same requirements on the IV as CBC mode.

- Should be randomized, and should not be predictable.

- Encryption

- Let $c_0$ be the initialization vector.

- $c_i = p_i \oplus E(k, c_{i - 1})$, where $p_i$ is the $i$-th plaintext block.

- The ciphertext is $(c_0, c_1, \dots)$.

- Decryption

- The first block $c_0$ contains the initialization vector.

- $p_i = c_i \oplus E(k, c_{i - 1})$. The same module is used for decryption!

- The plaintext is $(p_1, p_2, \dots)$.

- Advantages

- Appropriate when data arrives in bits/bytes (similar to stream cipher)

- Only encryption module is needed.

- Decryption can be run in parallel.

- Limitations

- Encryption is not parallelizable.

Error Propagation in CFB

- CFB mode is self-recovering.

- 1 bit error in the ciphertext corrupts some number of blocks.

- Bit errors in the ciphertext will cause bit errors at the same position.

- Since this ciphertext is fed to the next block, the error is propagated.

- Some implementations (like CFB-8) use shift registers, so errors will be propagated as long as the erroneous bit is in the shift register.

- If the error is removed from the shift register, it automatically recovers.

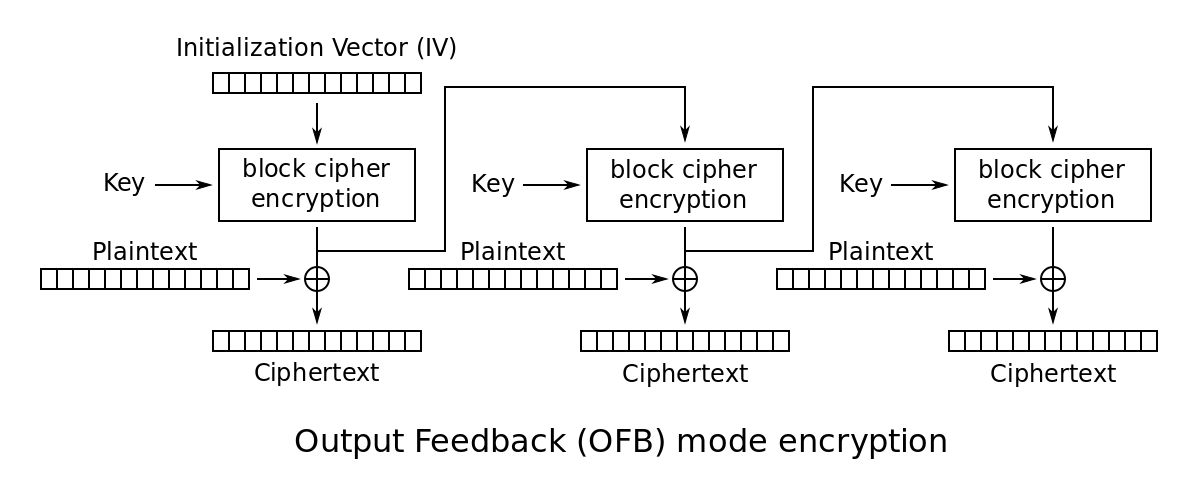

Output Feedback Mode (OFB)

- Very similar to stream cipher.

- Initialization vector is used as a seed to generate the key stream.

- Actual encryption and decryption only consists of XOR, so it is fast.

- Blocks are independent of each other

- Encryption/decryption are both parallelizable after key stream is calculated.

- Key stream generation cannot be parallelized.

- Encryption

- Let $s_0$ be the initialization vector.

- $s_i = E(k, s_{i - 1})$ where $s_i$ is the $i$-th key stream.

- $c_i = p_i \oplus s_i$.

- The ciphertext is $(s_0, c_1, \dots)$.

- Decryption

- The first block $s_0$ contains the initialization vector.

- $s_i = E(k, s_{i - 1})$. The same module is used for decryption.

- $p_i = c_i \oplus s_i$.

- The plaintext is $(p_1, p_2, \dots)$.

- Note: IV and successive encryptions act as an OTP generator.

- Advantages

- There is no error propagation. $1$ bit error in ciphertext only affects $1$ bit in the plaintext.

- Key streams can be generated in advance.

- Fast when parallelized.

- Only encryption module is needed.

- Limitations

- Key streams should not have repetitions.

- We would have $c_i \oplus c_j = p_i \oplus p_j$.

- Size of each $s_i$ should be large enough.

- If attacker knows the plaintext and ciphertext, plaintext can be modified.

- Same as in OTP.

- Key streams should not have repetitions.

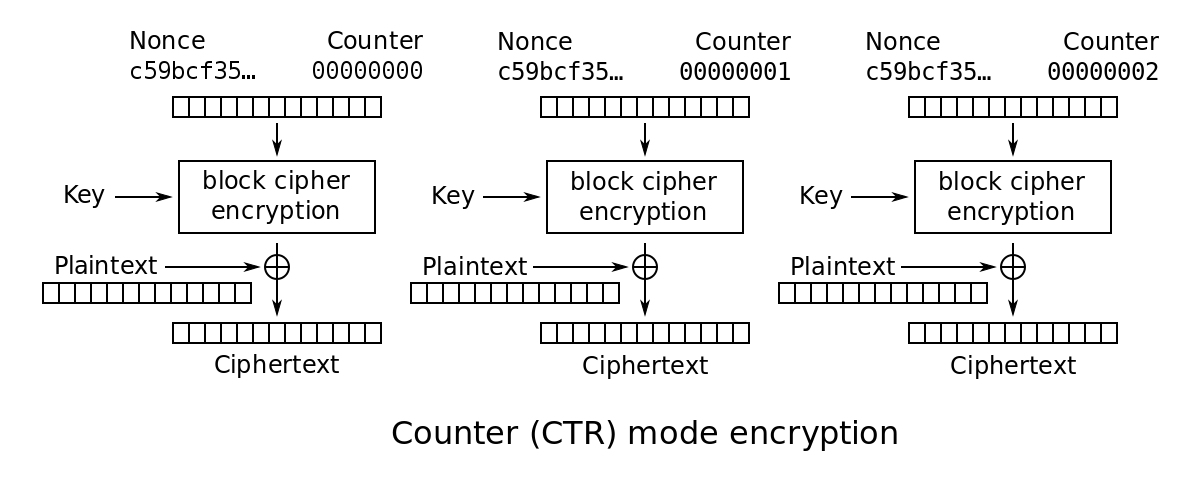

Counter Mode (CTR)

- Without chaining, we use a counter (typically incremented by $1$).

- Counter starts from the initialization vector.

- Highly parallelizable.

- Can decrypt from any arbitrary position.

- Counter should not be repeated for the same key.

- Suppose that the same counter $ctr$ is used for encrypting $m_0$ and $m_1$.

- Encryption results are: $(ctr, E(k, ctr) \oplus m_0), (ctr, E(k, ctr) \oplus m_1)$.

- Then the attacker can obtain $m_0 \oplus m_1$.

Modes of Operations Summary

| Criteria\Modes | ECB | CBC | CFB | OFB | CTR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV | - | Yes | Yes | Yes | Counter |

| Encryption Parallelizable | Yes | No | No | Yes* | Yes |

| Decryption Parallelizable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes* | Yes |

| Random Read Access | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Self-Recovering | - | Yes | Yes | - | - |

- OFB is parallelizable only if the keystream is generated in advance.

- We don’t have to consider self-recovery if the ciphertext is not fed into the encryption of the next block.

- Errors in the ciphertext are not be propagated for ECB, OFB and CTR.

- Random read access

- Suppose that a part of the plaintext changes.

- In OFB, the whole keystream must be recalculated to fix the ciphertext.

- But for other modes, only a part of the ciphertext needs to be changed, using the information from the previous block if necesary.

Images are from Wikipedia.